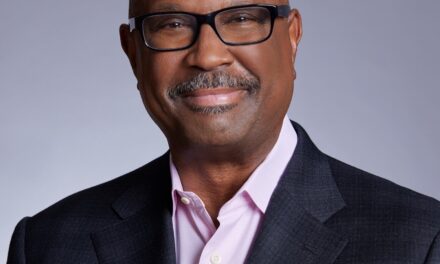

As a first-generation Black graduate student attending a large PWI research one university, I recognized the importance of leveraging my cultural assets to persist  Jason K. Segrestthrough my program. From mentors, professors, and members of my cohort, I realized that this journey is not meant to be traveled alone. Likewise, as a higher education professional, I have mentored and supported first-generation Black postsecondary STEM students who share similar life experiences, aspirations, challenges, and stories that help them persist through their STEM education and workforce readiness training. I write this op-ed based on experiences that align with my journey as a Black male doctoral student. I provide context about cultural capital assets and factors that contribute to their STEM identities.

Jason K. Segrestthrough my program. From mentors, professors, and members of my cohort, I realized that this journey is not meant to be traveled alone. Likewise, as a higher education professional, I have mentored and supported first-generation Black postsecondary STEM students who share similar life experiences, aspirations, challenges, and stories that help them persist through their STEM education and workforce readiness training. I write this op-ed based on experiences that align with my journey as a Black male doctoral student. I provide context about cultural capital assets and factors that contribute to their STEM identities.

For too long, negative stereotypes have fueled the belief that Black students lack preparedness for postsecondary STEM environments. These deficit narratives often highlight systemic obstacles like underfunded schools, limited exposure to STEM fields, and financial hurdles as explanations for why Black students are more likely to pursue non-STEM degrees and certificates. While these issues are substantial, they only tell part of the story.

To counter deficit narratives, first, we must acknowledge that first-generation Black STEM students have diverse cultural perspectives, foster innovative creativity, and demonstrate strong interest and resilience in various fields of STEM, as noted by Manning et al., and McGee and White. Researchers have asserted that Black students rely on cultural wealth assets grounded in their communities, families, and life experiences, fostering academic and professional growth. Acevedo & Solorzano and Yosso, Azmitia et al. asserted that first-generation Black students, in particular, demonstrate exceptional resilience, often overcoming obstacles in their personal and academic lives. Kornbluh et al. added that Black students who have experienced hardship usually develop critical skills to navigate and address adversity, equipping them to persist despite external challenges such as microaggressions, stereotype threats, and cultural differences.

Nevertheless, to better understand their success in postsecondary STEM education better, we must counter deficit narratives and advertise the strengths and cultural assets these students bring to their educational journeys. By capturing the stories of first-generation Black students, we uncover how cultural assets drive persistence and foster a sense of belonging in postsecondary STEM classrooms and fields where they have been historically marginalized and underrepresented. Below, I unpack two key elements: (1) how cultural wealth fosters persistence,and (2) how community cultural wealth contributes to the development of STEM identity.

Unpacking the Power of Cultural Wealth

Shifting from deficit-based narratives to an asset-based perspective, it is essential to unpack the definition of cultural capital. Yosso defined six forms of cultural capital often leveraged by ethnically and racially diverse students in academic spaces: aspirational; familial; social; navigational; resistant; and linguistic. These forms of capital are individual and unique, but they are collectively significant in supporting Black students in postsecondary STEM spaces. Manning et al.explained that aspirational capital is the ability to remain hopeful about one’s dreams and goals despite life’s challenges. Moreover, it has be noted that aspirational capital for Black students is linked to what family members or individuals they look up to inspire them to achieve their goals in postsecondary STEM education and careers.

Similarly, familial capital is vital for Black and other ethnically and racially diverse students who rely on their families for encouragement and support. Social capital is recognized as community resources and supports used for academic and personal support. For instance, Black STEM organizations such as NSBE (National Society of Black Engineers) and others are linked to social support to help first-generation Black students persist. Navigational capital is used to overcome challenges within institutions that are hostile to people of color. Resistant capital is closely aligned with navigational capital; however, considering that both challenge racist institutional norms and policies that hinder their academic aspiration. Lastly, linguistic capital is a means by which students from linguistically diverse backgrounds can communicate using their native language.

Cultivating STEM Identity Through Community Cultural Wealth

What does it mean to develop a STEM identity as a first-generation Black student while navigating academic and professional spaces where Black individuals have been historically underrepresented? I argue that creating a STEM Identity is associated with various contexts for first-generation Black students. I agree with Collins and Jones Roberson who state that building a STEM education is complex and usually based on race and gender, along with other factors influencing their decision to participate in STEM education at the postsecondary level and in their career fields. Moreover, concepts such as ‘belonging’ in STEM spaces, being recognized as a competent STEM person, and being acknowledged by their peers are significant (see Carlone & Johnson and Strayhorn et al. ). So, how does forming a positive STEM Identity connect with the factors of community cultural wealth? I argue that colleges and STEM instructors should create safe spaces for students to feel connected and welcomed in STEM spaces, allowing them to be authentic, while leveraging resources to help them succeed. Additionally, there is an opportunity for these institutions to develop cultural representation in STEM classrooms to mitigate microaggressions that Black students could face as minorities. This requires modifying the curriculum to be multicultural; culturally responsive – students of color are reflected and affirmed in the curriculum.

Overall, the opportunity to share my insights about this topic is rewarding and impactful. I developed this passion based on many interactions with Black two-year college students who were discriminated against simply for their cultural representation and the shortcomings of administrators, faculty, and other key staff members. STEM intervention programs such as the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (LSAMP) can act as a bridge and knowledge base to support Black students in their journey as capable STEM persons.

Jason K. Segrest is a doctoral student in the College of Education and Human Ecology at The Ohio State University.