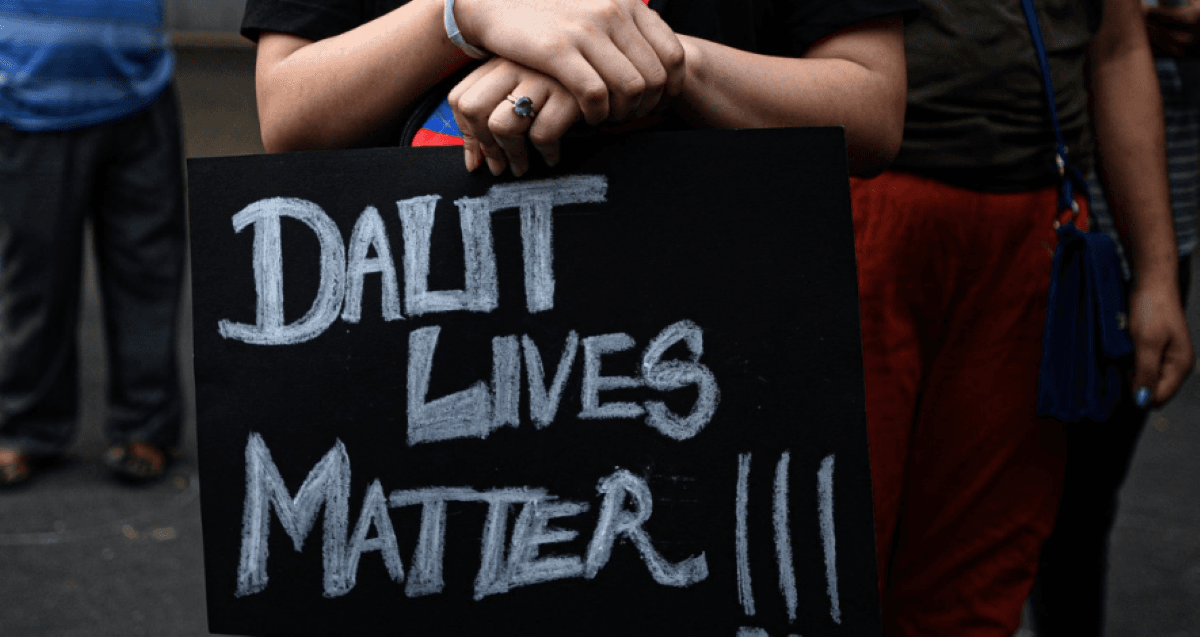

On January 17, 2016, a PhD candidate and a Dalit student of Central Hyderabad University died by suicide following his suspension from the University on account of a “complaint” by Akhil Bhartiya Vidyarthi Parishad. His name was Rohith Vemula. This suicide shook the Indian academia and the status quo with a note that repeated, “My birth was my fatal accident”

Student communities across the nation shook in protest against the systematic repression of Dalit, Adivasi and Bahujan in educational institutions. Eight years after this incident, the data from Business Standard reports a surge in suicide cases by 4 per cent annually, while the data on suicides of students from marginalised communities remain gravely underreported.

Exclusionary caste-based discrimination in Institutes

Prema Sridevi in her fieldwork on caste-based discrimination in India’s top institutes notes that the debate of so-called meritocracy often paves the way into the discourse of reservation and inclusivity with a claim of “dilution of their cherished standards.” The toll on the mental health of the students starts at the very introduction, where caste markers like language proficiency and unreserved category ranks label them as “preppies” at institutes like IITs. The discrimination goes on to shape a distinct lived experience for the marginalised where the savarna discourse dictates the forefront.

Source: AP

Source: AP

Sridevi continues that such discrimination continues even in basic amenities like hostel allocations contouring academic, social and mental aspects. A study by WatchOut reveals that supportive associations like SC-ST Cell in IIT-Bomaby and IIT-Delhi remain to be stagnant in their functioning. Similarly, cross-cultural study reveals that non-Hispanic Whites are more immune to depression than Black Americans. Caste, race, gender, and disability also become sites where mental health issues are more than often trivialised.

The fallacy of the Mental Health Care Act

Asia Society reports, “People from lower castes tend to experience depression 40 per cent more than the national average in India.” Moreover, access to mental health professionals and counselling is also a privilege that the Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi are denied time and again. These historically marginalised communities often occupy the lower income strata of society where affordability of mental well-being is also sceptical. This projects a serious lacuna in the legality of mental health in India. The Mental Healthcare Act of 2017 decriminalises attempted suicide and “provides for mental healthcare and services for persons with mental illness and to protect, promote and fulfil the rights of such persons during delivery of mental healthcare and services and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”

The act failed on various parameters including the addressing of inclusivity in mental health care and insurance of accessibility to mental health care facilities to marginalised students. Various surveys conducted both in rural and urban settings have established that the vulnerability of marginalised identity is composed of lived experiences where the subject experiences lower life satisfaction, prolonged depressive episodes, and higher odds of having psychological stress.

Living the history and suffering the present

The definition that the World Health Organisation gives to describe mental health issues is a “state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and can contribute to her or his community.” However, the structurality of caste is such that the inaccessibility to basic amenities is enforced to dictate the norm of hierarchy. This hierarchy is aided by violence that aims at dehumanising the social other.

Source: GLOBALVOICESONLINE

Source: GLOBALVOICESONLINE

The International Dalit Solidarity Network defines caste-hate speech as “any communication form such as speech, writing, behaviour, codes, signs, or memes that manifest hierarchies, invoke humiliation, serve to dehumanise, incite discrimination, degrade self-worth or perpetuate discrimination and are often the sources of physical, mental or material violence to a person or a group based on caste identity.” Within the academic space and even beyond that caste slurs filled with stereotypes related to socio-economic status. This discourse gets translated into praxis when people from marginalised communities remain underrepresented in academia on account of favouritism, nepotism and other relevant factors.

Samarveer Singh, a member of the other backward community and an ad-hoc assistant professor at Hindu College, died by suicide days after being displaced in the recruitment process for permanent posts. He taught at the college for years and was not accommodated due to academic politics. While foregrounding the issue of adhocism such cases also depict the amount of resilience that the hegemony demands from the marginalised communities to remain in the centre. The toll of savarna hegemony overpowers the resilience of the marginalised to the extent that they are often forced to leave academics altogether.

Inclusivity is a way to go

Community can play a pivotal role in bringing these issues to the forefront and addressing mental health through an inclusivity perspective. A paradigm shift in the approach of counselling along with policies of redressal of caste based discrimination can bring forth major reforms in the heart-wrenching statistics. Active SC-ST cells and progressive student associations are required for a sensitive and politically correct redressal. Joan Scott writes in The Evidence of Experience, “When experience is taken as the origin of knowledge, the vision of the individual subject becomes the bedrock of evidence on which explanation is built.”

The lived experiences of the marginalised must be prioritised in any discourse on mental health. The collectives must provide an alternative kinship structure that can become a ‘third place’ and a ‘secondary community,’ to its queer members that surpasses the boundaries of caste, religion, class, ethnicity, and language but doesn’t invisiblise these identities. Mental health apparatus should be made more accessible within the college premises. This involves regular mentor-mentee meet-ups and familiarising students from different social locations with each other outside the classroom. This also involves a realisation that higher education spaces can become a site to undo a lot of wrongs that schooling does including bullying, homophobia, and derogatory remarks of teachers among numerous other things. The diversity that higher education institutions provide must be harnessed to cultivate a culture of mental well-being and accommodation of those on the periphery.

References:

- Bakshi, Kaustav. Dasgupta, Rohit K. (2019) “Queer Kinship, Dissident Citizenship and Homonationational” in: Queer Studies- Texts, Contexts, Praxis

- Gupta, Aashish, and Diane Coffey. “Caste, Religion, and Mental Health in India.” Population Research and Policy Review, vol. 39, no. 6, May 2020, pp. 1119–41, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-020-09585-9.

- “Mental Health: The Spectre of Caste.” Asia Society, 2021, asiasociety.org/india/events/mental-health-spectre-caste. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

- Singh, Rimjhim. “Student Suicides in India Soar 4% Annually, Exceeding National Average.” @Bsindia, Business Standard, 29 Aug. 2024, www.business-standard.com/india-news/student-suicides-in-india-soar-4-annually-exceeding-national-average-124082900397_1.html.

- Sridevi, Prema. “Unveiling the Tragic Link: Caste Discrimination and Suicides in Higher Education.”

- Staff, Maktoob. “DU: Faculty Who Was Found Dead after Losing His Job Belonged to OBC Community.” Maktoob Media, 28 Apr. 2023, maktoobmedia.com/india/du-faculty-who-was-found-dead-after-losing-his-job-belonged-to-obc-community/. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.

- The Wire Staff. “My Birth Is My Fatal Accident: Rohith Vemula’s Searing Letter Is an Indictment of Social Prejudices.” Thewire.in, The Wire, 17 Jan. 2019, m.thewire.in/article/caste/rohith-vemula-letter-a-powerful-indictment-of-social-prejudices. Accessed 4 Oct. 2024.