The Legacy of Lynchings Still Hurts the Economic Prospects of Black Americans

Despite progress, the long shadow of racial violence continues to undermine economic opportunities for African Americans today

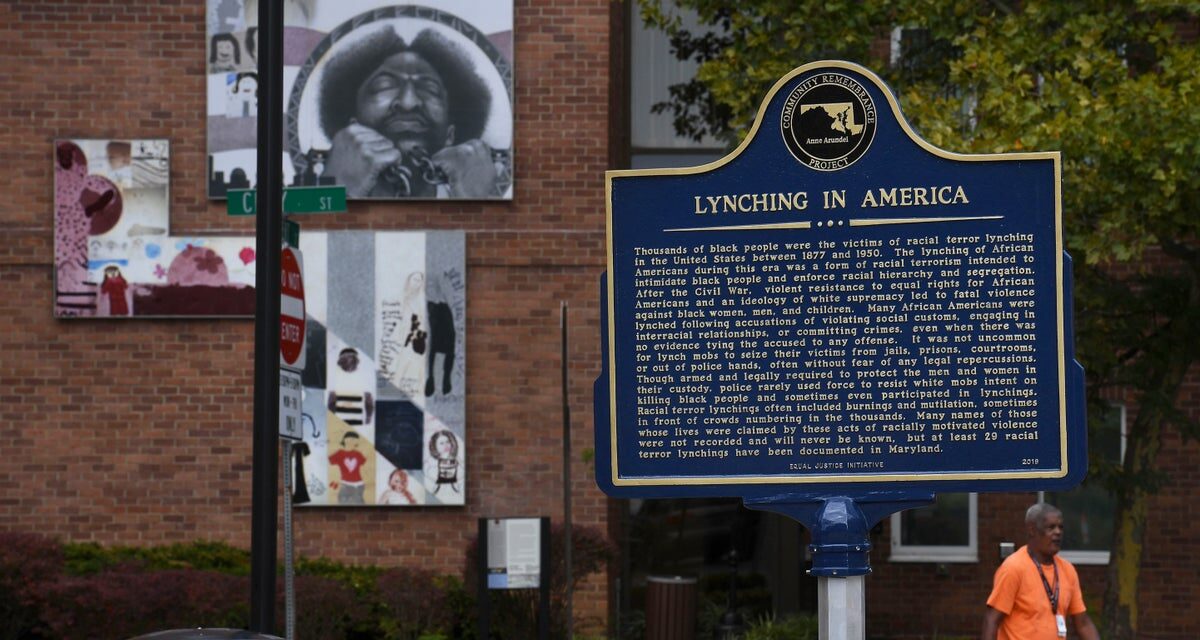

A historic marker detailing lynching in Anne Arundel County and in America at Whitmore Park on Calvert Street is seen September 17, 2019 in Annapolis, MD.

Katherine Frey/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Amid reports of record lows in unemployment for Black Americans and talk of “Black jobs” at June’s presidential debate, economic echoes of historical racism still resonate in the U.S. Today Black Americans face higher unemployment rates, lower earnings and deeper povertythan white Americans.

A legacy of injustice is most starkly evident in the economic disparities that persist in the places that were once plagued by lynchings.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, lynchings were widespread in the U.S., with more than 4,700 extrajudicial murders taking place from 1882 to 1968, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi shocked the nation and galvanized the early Civil Rights Movement.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These horrific acts still shape the economic landscape of many counties where the lynchings occurred. Today the legacy of lynchings hurts Black Americans’ economic prospects, limiting upward mobility and perpetuating a cycle of poverty. This is more than a historical anecdote; it’s an ongoing reality backed by rigorous research.

How do we know that? For a studypublished in June in Kyklos, I and my colleague looked at economic opportunity levels for Black individuals in counties with the highest rates of historical lynching. The economic difference between these regions and counties without a lynching history is as large as that between New Orleans and San Francisco; the median income in the latter is more than 170 percent higher. This contrast is significant, given the U.S.’s reputation as the “land of opportunity.”

Previous research by others has shown the lingering effects of lynchings. A 2021 study found that families of lynching victims were still suffering psychologically and economically decades and generations later. “We went from prosperity to poverty overnight,” the 77-year-old daughter of a victim told that study’s authors. The same year, in a paper in Health & Place, researchers looked at life expectancy in 1,221 counties in the U.S. South and found it was lower in those with a history of lynching by more than a year on average, compared with counties with no recorded lynchings.

The notion that anyone, regardless of their background, can achieve economic success through hard work is a cornerstone of the American dream. These findings, however, reveal a different reality for many Black people in the U.S., whose economic prospects are still heavily influenced by the legacy of racial violence and discrimination. The promise of equal opportunity remains elusive, highlighting the need for continued efforts to address these deep-seated inequalities. How accessible is the American dream when historical injustices endure and blight today’s prospects for prosperity?

One must consider the broader historical context to understand the persistent poverty and wreckage left by these murders and their mob terror. The rapid urbanization and industrialization that took place from 1880 onward exacerbated interracial competition for land, as well as for political and economic dominance at the local level. The migration of African Americans in search of better opportunities to urban centers increased tensions in these rapidly changing communities. White residents, fearing the loss of economic and social status, often responded with hostility and violence, including lynchings. Additionally, discriminatory practices such as redlining and job segregation further entrenched economic inequalities. In this volatile environment, tensions frequently erupted, reinforcing systemic racism and socioeconomic disparities for decades to come. The aftermath of the Tulsa race massacre of 1921—in which a white mob killed hundreds of men, women, and children and burned more than 1,250 homes over two days—exemplifies the “financial devastation” wrought by racial violence and its long-term ruin of survivors and their descendants. As a result of interracial tension and lynchings, Black families were often forced to flee their communities, abandoning social networks and losing valuable assets. This displacement caused immediate economic hardship and disrupted the accumulation of wealth and educational opportunities over generations. Consequently, the descendants of those affected by lynchings frequently find themselves trapped in a cycle of poverty, with limited opportunities for advancement.

Overall, as we continue to grapple with the legacy of racism in the U.S., it is crucial to recognize that the economic inequalities we see today are not merely the result of current policies or economic conditions. They are also a direct consequence of a long history of racial violence and discrimination that has systematically undermined the economic foundations of Black communities. Addressing the opportunity gap requires that we take a comprehensive approach that acknowledges and addresses the historical context of economic inequality. By doing so, we can begin to pave the way for a more equitable future, where the shadows of the past no longer dictate the opportunities of the present.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.