“Extremism is nothing new. It is woven into the American tapestry.” These words were written by an America columnist just as a presidential campaign was heating up. “Olympic contests of extreme meanness flourish” in our politics, the author lamented, but suggested there was a solution to the polarization that seemed to be seizing the nation:

Catholics, called to celebrate reconciliation instead of differences, must wonder what to do in an atmosphere where indifference to the problem might lead to moral culpability. Extremism, of whatever origin, can only be cured by balance—by shoring up the middle. Happily, the middle is fighting back on several fronts—political, spiritual and personal. One reaction to the moral challenge of extremism, it seems to me, is to salute such acts of leadership.

Wise words. They were written in 1995.

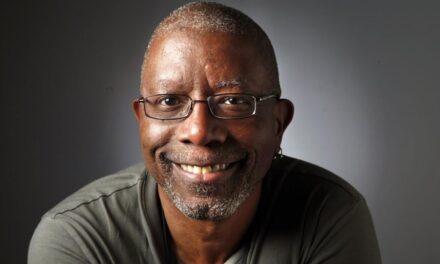

The author, Gail Lumet Buckley, who died on July 18 at the age of 86, also wrote in America at the time that “While my politics remain pluralistic (left, right and center), I choose the cross of faith over the sword of ideology. In honor of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. who saw justice as ‘bathed in love’—and in honor of Dorothy Day, who united conservatism and radicalism in love of Christ—I would like to change the name of this column to ‘As a Catholic.’”

Gail Lumet Buckley knew her way around American politics, history and media culture. The daughter of the famous actress, singer and civil rights activist Lena Horne (and the former spouse of director Sidney Lumet), she wrote an award-winning book in 1986 about the history of her African American family: The Hornes: An American Family. She followed it up three decades later with another critical success that focused on the history of two branches of her family: The Black Calhouns: From Civil War to Civil Rights With One African American Family.

In between, she authored several books and countless essays and reported pieces for numerous outlets. Her book American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military From the Revolution to Desert Storm was published in 2001 to critical acclaim. She also narrated a PBS documentary on African American families. (Readers can also watch her presentation on “A Chronicle of a Black Family Through the Ages” here.)

Born Gail Horne Jones on Dec. 21, 1937, in Pittsburgh, Pa., Lumet Buckley grew up in New York (well, Brooklyn) and Los Angeles. She graduated from Radcliffe College in 1959. After an internship in Paris at Marie Claire, she worked as a counselor for the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students and at Life. In 1963, she married the director Sidney Lumet; they divorced 14 years later. In 1983, she married the journalist Kevin Buckley, who died in 2021.

Lumet Buckley was a close friend of George W. Hunt, S.J., the editor in chief of America from 1984 to 1998. (America editors of another age often recalled the night that Lumet Buckley’s mother Lena Horne sang in the rec room at the old America House Jesuit community.) In addition to her column in the 1990s, Lumet Buckley wrote a number of book reviews for America in recent years, including a 2017 review of John Garofolo’s Dickey Chapelle Under Fire, a biography of Dickey Chapelle, a female war correspondent “with the terrible distinction of being the first American female correspondent to be killed in action.”

In a 2016 review of Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf’s biography of Thomas Jefferson, Most Blessed Of The Patriarchs, she noted that while Jefferson wrote as an old man that “the end of slavery will ever be my most fervent prayer,” his actions suggested otherwise. “If Jefferson’s actions in his prime had matched his words in old age he would truly have been the father of his country,” she wrote. “But Jefferson betrayed his own dream of American exceptionalism by helping to create (through inertia or self-interest) an ‘empire of slavery’ instead of the glorious republican ideal of universal freedom, throughout his beloved Virginia and the entire South.”

Ultimately, Lumet Buckley concluded, “Jefferson himself personified the eternal American dilemma: the conflict between the promise (of which Jefferson was a creator) and the practice.”

Lumet Buckley’s last book, Radical Sanctity: Race and Radical Women in the American Catholic Church, was published less than a year ago. It was on a subject close to her heart, a multibiography of four holy Catholic women who “chose to enter the American maelstrom of race”: Katharine Drexel, Dorothy Day, Catherine de Hueck Doherty and Sister Thea Bowman.

•••

Our poetry selection for this week is “Another Doubting Sonnet,” by Renee Emerson. Readers can view all of America’s published poems here.

Members of the Catholic Book Club: We are taking a hiatus this summer while we retool the Catholic Book Club and pick a new selection.

In this space every week, America features reviews of and literary commentary on one particular writer or group of writers (both new and old; our archives span more than a century), as well as poetry and other offerings from America Media. We hope this will give us a chance to provide you with more in-depth coverage of our literary offerings. It also allows us to alert digital subscribers to some of our online content that doesn’t make it into our newsletters.

Other Catholic Book Club columns:

The spiritual depths of Toni Morrison

What’s all the fuss about Teilhard de Chardin?

Moira Walsh and the art of a brutal movie review

Father Hootie McCown: Flannery O’Connor’s Jesuit bestie and spiritual advisor

Who’s in hell? Hans Urs von Balthasar had thoughts.

Happy reading!

James T. Keane