By Aria Brent

AFRO Staff Writer

abrent@afro.com

A June report shows that Black women disproportionately face postpartum maternal morbidity complications when compared to their White counterparts. The study, conducted by Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS), analyzed millions of Medicaid and commercial insurance reports from the University of Chicago National Opinion Research Center (NORC).

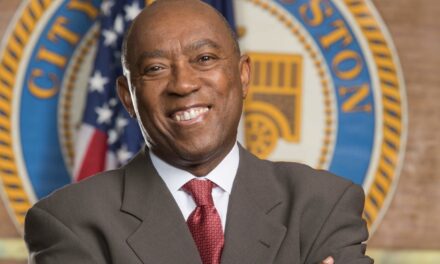

According to a recent report from the University of Chicago and Blue Cross Blue Shield, Black women face a greater risk of postpartum morbidity issues such as stroke and heart attack, when compared to their White counterparts. CREDIT: Nappy.co Photo / @Brit

According to a recent report from the University of Chicago and Blue Cross Blue Shield, Black women face a greater risk of postpartum morbidity issues such as stroke and heart attack, when compared to their White counterparts. CREDIT: Nappy.co Photo / @Brit

The report discussed the dangers many mothers face during labor, delivery and the postpartum period after birth, and found that Black women are at higher risk of severe maternal morbidity (SMM).

“Severe maternal morbidity represents very severe acute medical occurrences that happen during the postpartum period. Examples would be heart attack, stroke, admission to the ICU and the need for a blood transfusion,” said Dr. Nicole Saint Clair, executive medical director for Regence Blue Shield in Washington. “These are severe complications that have immediate repercussions and the potential for lifelong disability and other health complications.”

One local mother who dealt with the very real and scary effects of SMM, spoke with the AFRO about her postpartum experiences.

“With both of my pregnancies I experienced very traumatic births,” said Shannel Pearman, a stay-at-home mom of two from Parkville, Md. “I had postpartum preeclampsia in both of my pregnancies and with the first one, I had a stroke one week postpartum and I almost lost my life.”

Pearman said she started receiving hints of the trouble ahead before her baby was born.

“Towards the end of my first pregnancy, during the last week, I started experiencing some extreme weight gain in a short amount of time,” she recalls. “I was really swollen. I expressed my concerns, but unfortunately I feel as though my concerns weren’t heard.”

Pearman had her first child in May of 2019. She anticipated the time spent with her newborn baby as one of the happiest times in her life. Instead, she was left hospitalized and then permanently disabled.

The mother of two discussed the prevalence of stories like hers and how vital it is for Black women to advocate for themselves during medical emergencies.

“Unfortunately, my story is not unique,” said Pearman. “There’s so many Black women who are no longer here with us to tell their stories. There’s also many of them like myself, who are left with the scars of having traumatic birthing experiences.

“Black women have to advocate for themselves. If you feel like something is wrong, don’t just take what a doctor or a medical professional tells you,” she continued. “If you truly feel like something is wrong and your intuition is telling you that something’s not right–you have to speak up. Far too many Black mothers are suffering. What should be the happiest moments of their lives, unfortunately turns into some of the most terrifying.

“More needs to be done to uplift and support and advocate for Black moms,” she said.

Advocating for oneself is hard for some, especially when facing off against a healthcare professional with years of training and medical experience. However there are a series of resources available to help assure the voices of mothers are heard; one of the most popular being a doula.

Nyeema Wright, a postpartum doula from Long Beach, Calif., said one challenge facing mothers is a lack of education about resources available when it comes to doula services. Wright said that women are at a disadvantage by “not knowing about doulas, not knowing that we are here to be your companion throughout pregnancy throughout postpartum.”

“We are here to provide mothers with all of this well deserved education and well needed and deserved support,” she explained, adding that doulas serve as “the liaison between the provider and the parent.”

“That’s a crucial space to be filled and it’s necessary to have someone there outside of your family and friends. I am here, with all of my knowledge and my expertise–and I can tailor the care to fit every individual need,” said Wright.

According to the BCBS report, “postpartum SMM rates are 87 percent higher among Black patients and 7 percent higher among Latina patients in the commercially insured population.

The study included data from 2.9 million hospital deliveries from Jan. 2019 to Dec. 2022 through BCBS claims. Mothers with Medicaid accounted for another 6.2 million hospital deliveries studied between Jan. 2017 and Dec. 2021 by NORC. Researchers used claims from the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS).

The National Center for Health Statistics reveals the number of Black, White and Hispanic women who died in childbirth in 2019, 2020 and 2021. According to the data shown here, for every 100,000 live births, roughly 26 White and 28 Hispanic women lost their lives in 2021. In the same year, that number was 69.9 for Black women.

The National Center for Health Statistics reveals the number of Black, White and Hispanic women who died in childbirth in 2019, 2020 and 2021. According to the data shown here, for every 100,000 live births, roughly 26 White and 28 Hispanic women lost their lives in 2021. In the same year, that number was 69.9 for Black women.

Statistically significant increase from previous year (p < 0.05)

NOTE: Race groups are single race.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, Mortality.

The study found that “hospitalization rates are 71 percent higher for Black patients in the commercial population.”

Saint Clair discussed the research done and contributing factors to the increased rates of SMM and maternal mortality.

“As we follow both maternal mortality rates and morbidity rates, year after year, we see that Black women are at significantly increased risk compared to White women and all other ethnicities for both complications,” she said. “Black women continue to be two to three times more likely to experience either issue. And when we look at what the factors are, it’s really multifactorial.”

“There are issues in quality health care, as well as the presence of underlying conditions,” said Saint Clair, adding that there needs to be a focus on “what’s happening in the lead up to the pregnancy,” especially when knowledge of disparities exist.

“We know that there are many components of structural racism and implicit bias that really manifest in a variety of different ways,” said Saint Clair.

In a 2022 report, titled “How Implicit Bias Contributes to Racial Disparities in Maternal Morbidity and Mortality in the United States,” implicit bias is defined as “attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.”

The report explained that implicit bias can have disastrous results, and often comes into play “in settings that are prone to overload or high stress,” such as “emergency departments or labor and delivery settings, where relying on automatic or unconscious processes to execute medical decision making quickly becomes essential.”

The automatic components to high-stress decision making “are likely to activate stereotypes and unconscious beliefs. In addition, cognitive stressors, such as overcrowding and the demand to care for more patients during a shift, are associated with an increase in implicit bias.”

All of this can make the labor and delivery room more dangerous for Black women, who face a plethora of stereotypes as they conceive, carry, deliver and care for their children.

To make matters worse, while doctors are aware of the disparities, they don’t see their own contributions to the problem.

The 2022 implicit bias study used research from the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, which showed “inconsistency between clinicians’ willingness to acknowledge disparities in their practice and their consideration of implicit bias.”

Researchers found that “84 percent of respondents agreed that disparities affect their practice, but only 29 percent believed that personal biases influenced their ability to care for patients.”

In efforts to fight inequality in the healthcare system, BCBS has created a public health platform that calls for those in power to:

- Improve access and affordability by working to “remove barriers to Medicaid enrollment retention for eligible Americans,” while also improving access to telehealth. BCBS says that “insurance through tax credits that keep Marketplace plans affordable for those who need them” is also crucial.

- Address and mitigate the impacts of social drivers of health (SDOH) to combat the effects of health inequity. SDOH can account for over 50 percent of a person’s well-being. Access to enough food, access to healthy food options, a lack of access to transportation and unstable housing are some of the most common social determinants of health. Marginalized communities are more likely to experience some of these dangerous social drivers.

- Build an equitable health care workforce by investing in initiatives such as educational pathways, to expand and diversify the workforce. Fostering the partnerships between public-private organizations is vital to creating a more equitable health care environment. Additionally, expanding peoples accessibility to non-physician practitioners is necessary when aiming to create more equitable healthcare systems.

- Harness and standardize health equity data to help lessen health disparities and measure progress. The government can directly help by providing funding to the CDC to create, coordinate and manage state-based review committees to recognize, review and characterize pregnancy-related morbidity. Assuring that data is collected without bias and directly from patients is vital to the standardization of data.

To view the full BCBS report, click here. For more information on how to combat the issues of Black maternal morbidity and mortality visit cdc.gov/hearher.