SEATTLE — A federal judge on Thursday temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order denying U.S. citizenship to the children of parents living in the country illegally, calling it “blatantly unconstitutional” during the first hearing in a multistate effort challenging the order.

The 14th Amendment to the Constitution promises citizenship to those born on U.S. soil, a measure ratified in 1868 to ensure citizenship for former slaves after the Civil War. But in an effort to curb unlawful immigration, Trump issued the executive order just after being sworn in for his second term on Monday.

The order would deny citizenship to those born after Feb. 19 whose parents are in the country illegally. It also forbids U.S. agencies from issuing any document or accepting any state document recognizing citizenship for such children.

Trump’s order drew immediate legal challenges across the country, with at least five lawsuits being brought by 22 states and a number of immigrant rights groups. A lawsuit brought by Washington, Arizona, Oregon and Illinois was the first to get a hearing.

“I’ve been on the bench for over four decades. I can’t remember another case where the question presented was as clear as this one is,” U.S. District Judge John Coughenour told a Justice Department attorney. “This is a blatantly unconstitutional order.”

“There is a strong likelihood that the Plaintiffs will succeed on the merits of their case,” the judge wrote in his four-page decision.

Thursday’s decision prevents the Trump administration from taking steps to implement the executive order for 14 days. In the meantime, the parties will submit further arguments about the merits of Trump’s order. Coughenour scheduled a hearing on Feb. 6 to decide whether to block it long-term as the case proceeds.

Coughenour, 84, a Ronald Reagan appointee who was nominated to the federal bench in 1981, grilled the DOJ attorney, Brett Shumate, asking whether Shumate personally believed the order was constitutional.

“I have difficulty understanding how a member of the bar could state unequivocally that this is a constitutional order,” he added.

Shumate assured the judge he did — “absolutely.” He said the arguments the Trump administration is making now have never previously been litigated, and that there was no reason to issue a 14-day temporary restraining order when it would expire before the executive order takes effect.

The Department of Justice later said in a statement that it will “vigorously defend” the president’s executive order, which it said “correctly interprets the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.”

“We look forward to presenting a full merits argument to the Court and to the American people, who are desperate to see our Nation’s laws enforced,” the department said.

The case is one of several lawsuits challenging Trump’s executive order, which the president said would take effect in mid-February. Another coalition of 18 states and the District of Columbia filed a similar lawsuit in Massachusetts, and at least three civil-rights groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union, are pursuing their own legal challenges.

In the coming days, legal experts said, Coughenour could seek to extend the temporary restraining order or issue a preliminary injunction that would put the executive order on pause as the case is adjudicated in his courtroom. The issue could ultimately land in the Supreme Court, where Trump had a mixed record on immigration-related cases during his first term.

“We’re gratified to see the restraining order. It is temporary, so the cases will proceed, including our case,” Cody Wofsy, lead attorney for the ACLU’s challenge of Trump’s executive order, said of the Seattle court’s decision. “But the fact that we’re seeing all these cases around the country speaks to how dramatic this attempt to undo a core constitutional value is and how widespread the impacts are.”

The U.S. is among about 30 countries where birthright citizenship — the principle of jus soli or “right of the soil” — is applied. Most are in the Americas, and Canada and Mexico are among them.

The 14th Amendment was ratified in 1868, in the aftermath of the Civil War, to ensure citizenship for former slaves and free African Americans. It states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Trump’s order asserts that the children of noncitizens are not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, and therefore not entitled to citizenship.

In the lawsuit filed in federal court in the Western District of Washington, attorneys for the four states said the order violates the Constitution and argued that thousands of newborns in their jurisdictions would be harmed each year. Across the country, the filing states, an estimated 153,000 children are born to two undocumented parents annually.

The attorneys argued that their states would be required to undertake “disruptive” new operational and administrative burdens to help enforce the new policy and would lose revenue from the federal government to help provide Medicaid and other public benefits for children who are affected.

“The individuals who are stripped of their United States citizenship will be rendered undocumented, subject to removal or detention, and many will be stateless — that is, citizens of no country at all,” the filing states, adding that they “will be placed into lifelong positions of instability and insecurity as part of a new underclass in the United States.”

The Trump administration responded in a court filing late Wednesday that the states lack legal standing to sue the federal government. Justice Department attorneys also argued that the executive order does not require state governments to pay for public benefits for the children who are denied citizenship or to undertake new administrative procedures.

“These asserted harms are greatly outweighed by the harm to the government and public interest that would result from the extraordinary relief Plaintiffs request,” according to the administration’s response to the lawsuit. “As the Supreme Court has recognized, Executive officials must have ‘broad discretion’ to manage the immigration system.”

Arguing for the states on Thursday, Washington assistant attorney general Lane Polozola called that “absurd,” noting that neither those who have immigrated illegally nor their children are immune from U.S. law.

“Are they not subject to the decisions of the immigration courts?” Polozola asked. “Must they not follow the law while they are here?”

Polozola also said the restraining order was warranted because, among other reasons, the executive order would immediately start requiring the states to spend millions to revamp health care and benefits systems to reconsider an applicant’s citizenship status.

“The executive order will impact hundreds of thousands of citizens nationwide who will lose their citizenship under this new rule,” Polozola said. “Births cannot be paused while the court considers this case.”

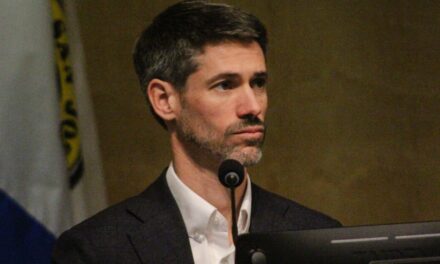

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown told reporters afterward he was not surprised that Coughenour had little patience with the Justice Department’s position, considering that the Citizenship Clause arose from one of the darkest chapters of American law, the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which held that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, were not entitled to citizenship.

“Babies are being born today, tomorrow, every day, all across this country, and so we had to act now,” Brown said. He added that it has been “the law of the land for generations, that you are an American citizen if you are born on American soil, period.”

“Nothing that the president can do will change that,” he said.

A key case involving birthright citizenship unfolded in 1898. The Supreme Court held that Wong Kim Ark, who was born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrants, was a U.S. citizen because he was born in the country. After a trip abroad, he had faced being denied reentry by the federal government on the grounds that he wasn’t a citizen under the Chinese Exclusion Act.

But some advocates of immigration restrictions have argued that case clearly applied to children born to parents who were both legal immigrants. They say it’s less clear whether it applies to children born to parents living in the country illegally.

Trump’s order prompted attorneys general to share their personal connections to birthright citizenship. Connecticut Attorney General William Tong, for instance, a U.S. citizen by birthright and the nation’s first Chinese American elected attorney general, said the lawsuit was personal for him. Later Thursday, he said Coughenour made the right decision.

“There is no legitimate legal debate on this question. But the fact that Trump is dead wrong will not prevent him from inflicting serious harm right now on American families like my own,” Tong said this week.

Separately, Rep. Brian Babin, R-Texas, joined a group of GOP lawmakers in announcing legislation Thursday that they said would codify Trump’s executive order into law. The bill proposes amending the Immigration and Nationality Act to “clarify” who qualifies for citizenship upon birth.

He said supporters of Trump’s birthright citizenship ban welcome the legal challenges to the directive “so that we can get it into the Supreme Court of the United States.”

Information for this article was contributed by Gene Johnson, Mike Catalini and Alanna Durkin Richer of The Associated Press and by David Nakamura and Brianna Tucker of The Washington Post.

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

A person films Washington Attorney General Nick Brown as he speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

A person films Washington Attorney General Nick Brown as he speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown arrives for a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown arrives for a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, on Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a news conference announcing that Washington will join a federal lawsuit to challenge President Donald Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a news conference announcing that Washington will join a federal lawsuit to challenge President Donald Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship Tuesday, Jan. 21, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on birthright citizenship in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

President Donald Trump signs an executive order on birthright citizenship in the Oval Office of the White House, Monday, Jan. 20, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Washington Attorney General Nick Brown speaks during a press availability after a federal judge temporarily blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order aimed at ending birthright citizenship in a case brought by the states of Washington, Arizona, Illinois and Oregon, Thursday, Jan. 23, 2025, in Seattle. (AP Photo/Lindsey Wasson)

Source