In this presidential election season, alongside critical issues such as gun control and reproductive rights, the concept of reparations for Black Americans stands as another urgent challenge.

The U.S. State Department defines reparations, also known as “reparative justice,” as a crucial component of providing justice to victims of severe human rights abuses or atrocities. It’s a framework that seeks to address the enduring legacy of over 400 years of enslavement and its subsequent devastating impact on Black people.

“Reparations are a blueprint for collectively repairing gross human rights violations–including chattel slavery, genocide, war crimes, white supremacist violence, land theft, forced sterilization, medical experimentation, incarceration and police brutality,” explains Dr. Amara Enyia, a leading strategist and public policy expert. As president of the transnational advocacy organization Global Black and director of Policy & Research for the Movement for Black Lives, she outlines five essential components of reparations:

- Satisfaction: Acknowledging and truthfully addressing the historical injustices inflicted upon Black people and receiving an accepted response.

- Compensation: Providing monetary restitution for economic losses stemming from these harms.

- Restitution: Restoring freedom, reuniting families and recognizing the humanity, identity and culture of Black people.

- Rehabilitation: Offering care and support for healing from the trauma caused by these injustices.

- Cessation and Non-repetition: Transforming systems and structures to prevent the recurrence of such harms.

The first documented account of reparations for Black Americans occurred in 1783 when the formerly enslaved Belinda Sutton was granted a yearly pension of 15 pounds and 12 shillings from the estate of her former enslaver, Isaac Royall, after being enslaved for 50 years.

In 1865, Union General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 allocated 400,000 acres of confiscated Confederate land to Black families. Conceived by Black leaders of the time and often referred to as “40 acres and a mule,” it was designed to foster integration and economic independence for America’s newly freed people. However, President Andrew Johnson’s subsequent reversal of this order returned the land to its former Confederate owners.

The establishment of a comprehensive national reparations plan for Black Americans is increasingly seen as crucial for addressing the persistent wealth gap between Black and white communities. As William Darity Jr., a leading expert on inequality and reparations, notes, “The disparity in wealth between Black and white Americans continues to widen, underscoring the urgent need for a comprehensive national reparations program. Between 2019 and 2022 alone, the difference in net worth between the average white and Black household soared from $840,900 to $1.15 million.”

Darity, the Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy at Duke University, who is renowned for his extensive research on inequality, economic disparities and the historical and economic implications of enslavement and its aftermath, points out that a sense of urgency over persistent crisis conditions in Black America should not dominate the need to get it right on reparations.

“We should not settle for less than is merited, like piecemeal state and local initiatives that are falsely parading under the label of reparations,” concludes Darity, who is one of the editors of Black Reparations: Insights from the Social Sciences Part I & II, a new research journal published by the Russell Sage Foundation.

The goal of reparations is to compensate the 40 million descendants of enslaved people, which would be no easy task. But as the call grows stronger, understanding where the current presidential candidates stand on reparations is imperative.

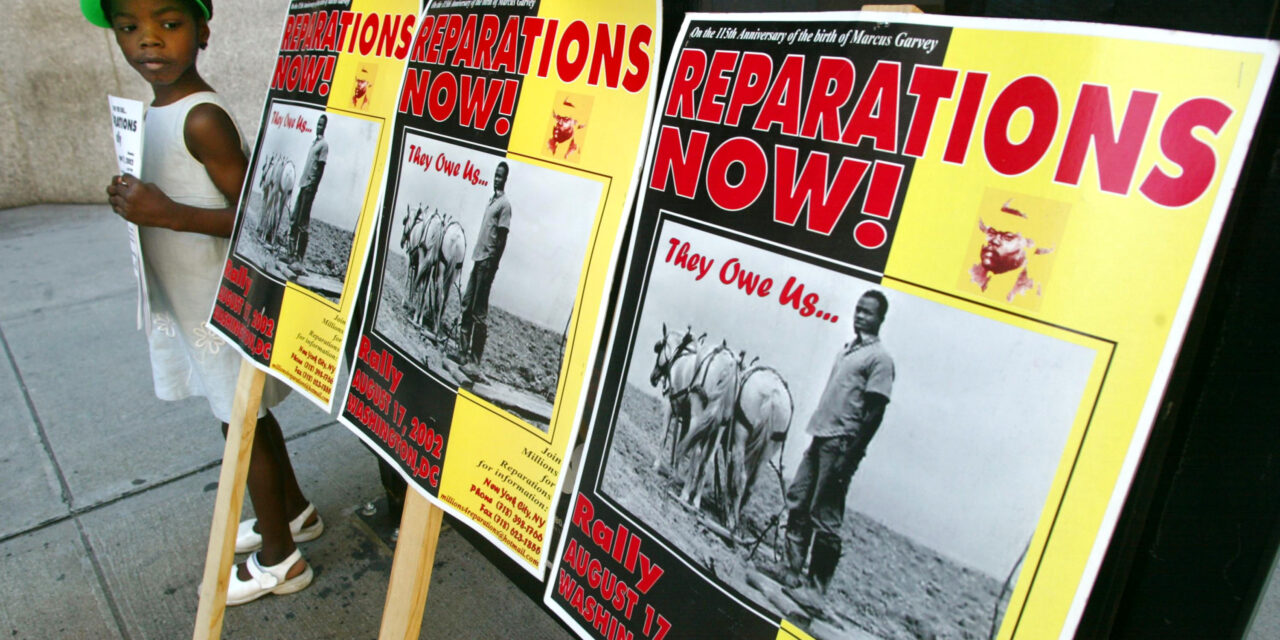

Image: Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Image: Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

Presumed Democratic presidential candidate Vice President Kamala Harris recently stated to The Root, “I think there has to be some form of reparations, and we could discuss what that is, but look, we’re looking at more than 200 years of slavery…We’re looking at almost 100 years of Jim Crow. We’re looking at legalized segregation and, in fact, segregation on so many levels that exist today based on race and there has not been any kind of intervention done understanding the harm and the damage that occurred to correct [the] course. And so we are seeing the effects of all those years play out still today.” If elected as president, Harris has said she would lead a conversation on how reparations could be formulated.

In contrast, Republican candidate and former President Donald Trump made this statement to The Hill during his administration in 2019: “I don’t see it happening,” as Democratic members of Congress pushed for research on providing reparations for enslaved descendants. “It’s been a very interesting debate. I don’t see it happening, no.”

Dr. Enyia argues that reparations encompass far more than monetary compensation. “Black people in the U.S. and around the world are still owed the acknowledgment, compensation, restitution and rehabilitation for all of the harms that flowed from our enslavement, and for all of the wealth built on our stolen lives, labor, colonization and torture,” she declares.

“In the United States, reparations are owed for the continuing impacts and harms that flow from chattel slavery and anti-Blackness, including Jim Crow (apartheid), white supremacist violence, health injustices, epidemic genocide, segregation, land theft, housing discrimination, environmental racism, educational injustice, mass criminalization and incarceration, detention and deportation, The War on Drugs and discriminatory enforcement of prostitution laws, police violence and violence against people in prison, on probation and on parole, and immigration detention and deportation. Any policy that fails to acknowledge, assess and address past harms is destined to recreate them.”

Thomas Craemer, a public policy associate professor at the University of Connecticut and fellow author of the reparations journal, underscores the urgency of tangible action. “I think any federal reparations bill should contain not only ‘a conversation’ or a ‘commission to study reparations.’ Much research has already been done,” he states, adding that it is time for a down payment large enough to close the national average per-capita Black-white wealth gap.

While states like Illinois, New York and California have been leaders in the effort to establish a reparations plan, Dr. Enyia emphasizes that a groundswell of support has been at the municipal level. Cities across the nation are actively exploring reparations commissions to address historical wrongs.

However, Craemer cautions that the scale of the issue demands a federal solution. “The federal government commands vastly more resources than any individual state or local jurisdiction. Since all levels of government (as well as corporate persons and individuals) were complicit in these atrocities, all should join forces providing reparations for slavery and post-slavery anti-Black race discrimination now,” he insists.

Reparations legislation may not be an official measure on the November ballot, but its fate could depend on who wins the White House. And the outcome could significantly shape how the nation moves forward on reckoning with its unjust racial past.