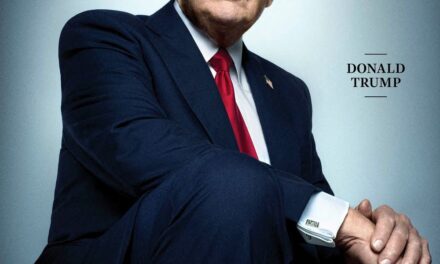

Jordon Crawford, a Du Bois Freedom Center fellow and Ph.D. student at the Du Bois Department of African American Studies at UMass Amherst tells visitors on Saturday about the significance of A.M.E. Zion churches to the Black community. Crawford spoke during a tour of the former church in Great Barrington that is being preserved and renovated to house the Du Bois Freedom Center.

HEATHER BELLOW — THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

GREAT BARRINGTON — The former Clinton A.M.E. Zion Church building on Elm Court, once the center of its community, has been stripped to its studs and will soon be propped up with steel beams and cross timbers.

The peeled-back paint on one wall in what was once the sanctuary reveals most of the letters of the words: “The Lord Is In His Holy Temple.”

And there are some holes in the wooden floors on which generations of the town’s African American community stepped as they flowed in and out for well over a century.

Including, at one point, town native W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois went on to be a scholar, writer, poet, professor and the architect of the civil rights movement as a co-founder of the NAACP.

Visitors got a tour Saturday morning to see the restoration efforts at the former church building, soon-to-be the Du Bois Freedom Center. Its Executive Director, Ny Whitaker, is offering tours on Saturdays on a limited basis through September.

The Du Bois Freedom Center’s Executive Director Ny Whitaker hosted a tour on Saturday morning and told visitors about the restoration work as well as the role of the organization inside the former Clinton A.M.E. Zion Church building in Great Barrington.

HEATHER BELLOW — THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

The Du Bois Freedom Center is 10 years in the making after former members of the church began an effort to restore it and turn it into a community center and “hub” for African American heritage in the Berkshires and larger region.

With the first phase of stabilizing the building and roof nearly completed, the next phase will tackle the renovation, Whitaker said. The doors of a fully finished Du Bois Freedom Center should be open in two to three years.

A capital campaign will soon commence seeking for $5 million to $7 million to complete the project, Whitaker added. It has received nearly $2 million in grants over the last 10 years for this first phase to stabilize the building.

But already the center has begun its work, partnering with other organizations, and holding its “Reflections on Democracy” events with guest speakers at Saint James Place on Main Street. On Sept. 19, for instance, the event will feature the writer and award-winning Leslie Odom Jr., noted for his role in the musical “Hamilton.”

Once completed, the center will focus on the legacy of Du Bois and launch a “scholar/activist” institute, said Whitaker, an “Obama Scholar” — she served as a senior advisor in former President Barack Obama’s administration.

The top floor and former sanctuary of the Clinton A.M.E. Zion Church in Great Barrington during a Saturday tour. The church was deconsecrated in 2014 and is undergoing preservation and renovation efforts for the home base of the Du Bois Freedom Center, a hub of African American heritage.

HEATHER BELLOW — THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

Whitaker was joined in the tour by Jordon Crawford, a Du Bois Center fellow and Ph.D. student at the Du Bois Department of African American Studies at University of Massachusetts Amherst. Crawford is also a Methodist minister who is from Jamaica.

Crawford noted that the Clinton church and other A.M.E. churches was not just for worship. In the years after it was built in 1886, Crawford said, it was also the center of community.

“It was a spiritual, cultural and political heart of Black life in the Great Barrington and the region,” Crawford added, noting that the church was “a focal point” of social and political activism during the Jim Crow era and hosted NAACP meetings in the 1950s and 1960s.

After the tour of the building on Saturday, visitors from several states and Du Bois Freedom Center officials posed for a photo outside the historic church building in downtown Great Barrington.

HEATHER BELLOW — THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

Those who were congregants say it was the late Rev. Esther Dozier who understood the significance of saving the historic building.

“This was her life,” said Virginia Conway, a member of the congregation for more than 40 years and now on the Du Bois Center’s board. “She and her husband put so much work into this church.”

Conway told The Eagle that it was Dozier, the first female pastor here, who kept the fire of Du Bois remembrance alive in a town that ignored his legacy for decades. The church under Dozier’s leadership held an annual celebration on his birthday.

Dozier, Conway added, was also fierce in protecting the building so that it could be added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008.

Project architect Steve McAlister told visitors that Dozier and her congregation kept the building going with little money — as did the earlier generations. This gave his team something to work with, “to bring it to shore safely so that we can do what we’re doing now.”

Project architect Steve McAlister tells visitors on a tour about the historical research and forensics of preserving and renovating the historic Black church in Great Barrington that will become home to the Du Bois Freedom Center.

HEATHER BELLOW — THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE

He also explained that the project involves “forensics” and historical research. Crews are peeling back the layers of history and are working to keep what was essential to the “life of the church.”

Creating that church life was a struggle. “Most of the work in the church was done by hand,” Whitaker said, “so you have to think about that time and that the members would not have had access to loans from a bank.”

The basement, Whitaker noted, members had “dug out by hand.” That basement is a wet one, and so the project involves jacking it up with to with those steel beams. There are lots of stories, Whitaker said of members over the years who “were in the basement with buckets and mops trying to get the water out that was flooding the community space.”

“That was the space for ice cream socials and fish fries and meetings [and] conversations,” Whitaker said, “that you couldn’t have outside the walls and the doors about ways that they wanted to organize to support the Black community.”