The state has fully approved nearly 40 other AP courses, including European History and Spanish Literature and Culture. While school districts can offer a non-AP African American or Black studies course and use state funding, the state is still refusing to add AP African American Studies to its list of fully approved courses.

The only difference between AP African American Studies and Georgia’s fully approved AP courses is the focus on Black Americans, a major portion of America’s population that has faced oppression, was enslaved, and was at the center of the U.S. Civil War and our nation’s legacy of efforts at social justice.

The topics covered in AP African American Studies are essential knowledge for all students in preparation for college and the workforce. The last-minute decision from the state superintendent also wreaked havoc on school schedules across the state. Most public schools in metro Atlanta start school this week.

The state’s stubborn failure to approve AP African American Studies means access to the course is unequal for students across the state. This is unacceptable.

The Atlanta Public Schools, about 30 schools in other areas of Georgia, and schools in other parts of the country piloted the AP course last year. Georgia students had already signed up for the course, and teachers have prepared to teach it. To our knowledge, the piloting of the AP course in Georgia was a success.

Even Gov. Brian Kemp is questioning the state superintendent’s decision, saying that schools and families should make decisions about education at the local level. How much local control is available when the state is blocking full access to this course?

The state superintendent has unnecessarily made the AP African American Studies course controversial, when allowing schools to offer the course shouldn’t have warranted a second thought. The Georgia Department of Education’s attempted clarifications do not resolve the issue.

The very reason that African American Studies has become a well-established field — with even its own section in many bookstores — is because Black people were intentionally omitted from most textbooks and classroom materials in the South until the 1970s and 1980s.

How can any student fully understand the American story without knowing that Black people were enslaved until the 1860s and routinely faced acts of violence and terror more than 150 years afterward? Or that Black students were barred by law from attending the same schools as white students in Georgia and many parts of the South as late as 1970 and within my lifetime?

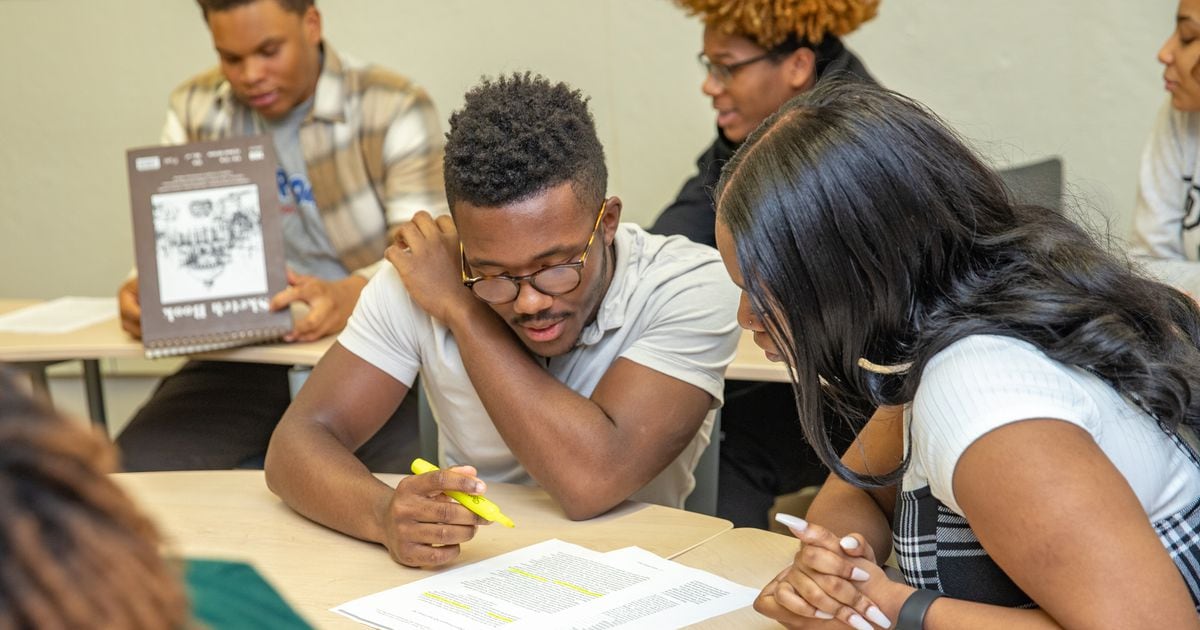

AP courses are developed by the College Board in consultation with leading scholars and classroom teachers across the country. Disproportionately few Black students take AP courses nationwide, and this new course may be the most appealing and engaging one ever offered for Black students — and any other students.

Consider that only about 9% of students in AP courses nationwide are Black, along with only 2% of students in AP biology, chemistry and physics, the Education Trust has found.

The failure to approve this AP course, and the other efforts to bar or remove discussions of race in American classrooms, threatens our racial progress as a nation. After all, this is Georgia, home to one of the largest Black populations in the country. Atlanta had a central role of course in the Civil Rights Movement.

Our leaders here in Georgia should be protecting students’ right to learn without political censorship or interference, not subjecting all of us to some narrow-minded, extreme political ideology.

The decision to treat this AP course differently than others — and the students, educators and communities that wish to participate — simply cannot stand. If the state superintendent doesn’t immediately change his decision, the state Board of Education should do it for him.

Raymond C. Pierce is the president and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation (SEF), a nonprofit, nonpartisan, 157-year-old organization based in Atlanta that works to make education opportunity more equitable for historically underserved students of color and students from low-income families. An attorney and former law school dean, Pierce has also served as deputy assistant secretary in the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.