In commemoration of City Weekly’s 40th anniversary, we are digging into our archives to celebrate. Each week, we FLASHBACK to a story or column from our past in honor of four decades of local alt-journalism. Whether the names and issues are familiar or new, we are grateful to have this unique newspaper to contain them all.

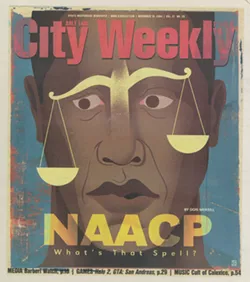

Title: NAACP: What’s That Spell?

Author: Don Merrill

Date: Nov. 18, 2004

I’m black, and for me the NAACP is an icon.

To those who know it, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People needs no introduction. Founded in 1909, the NAACP fought racial discrimination whenever it occurred. After losing a case to defend a black farmhand who killed a police officer in self-defense, it organized a nationwide protest against the biggest box-office hit of the time, D.W. Griffith’s bigoted Birth of a Nation. The NAACP successfully pushed President Woodrow Wilson to condemn lynching in 1918, successfully sued the University of Maryland to admit a black student in 1935, and won its most famous legal battle in 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education in an attempt to end segregation in public schools.

Throughout its history, NAACP members have endured insults, taunts, beatings, death threats and even death itself, most notably in the 1963 assassination of Mississippi field director Medgar Evers. In the 1990s, it helped quash former Klan leader David Duke’s aspirations for governor of Louisiana.

Utah’s first NAACP branch incorporated in 1919 in Salt Lake City. Along with its younger Ogden Branch, the two lobbied to end housing discrimination. And when a Boy Scout troop under the sponsorship of the LDS Church refused to give leadership roles to two black Scouts in 1974, the Salt Lake Branch filed suit.

As a rule, black people aren’t supposed to question the NAACP. To do so is to practically turn in your “black” card. Witness the firestorm of protest against comedian Bill Cosby earlier this year. But while writing this story about the Salt Lake Branch of the NAACP, my interviews revealed that perhaps some things did need fixing. I learned that Salt Lake City’s black community is as fractured as a windshield from a head-on crash. But at least some people from different groups can agree on what made the wheels come off.

The Leadership

Jeanetta Williams is elegant. She bespeaks of style in dress and confidence in manner. Members of the Salt Lake Branch of the NAACP know of her confidence as well, having chosen seven-times to elect her branch president.

She best demonstrated her durability by defeating both recent challenger Larry Houston and 2002 challenger Alberta Henry. Some say Henry was the last in a line of “old school”-style branch leadership. Her legacy, an ongoing fight against discrimination in the Salt Lake City schools, is legendary.

But Henry won’t talk about Williams. All she’ll say is how folks she knows feel about the organization. “They mad at it. Ooooh, they mad!” she says.

Many felt Henry’s warm and folksy communicative style represented the type of leadership that emphasized community and inclusion, as opposed to the Salt Lake Chapter’s recent shift toward a corporate emphasis. And because some of the membership was dissatisfied with Williams’ leadership style, they mounted an effort to unseat her with Henry. That didn’t sit well with other pillars in the community, like Danny Burnett. At 74, he’s spent practically his whole life involved in the Salt Lake Branch. He was its second, paid Life Member. He received the prestigious Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Award in 1985, and ran the local NAACP Youth Branch for many years. His feelings on the 2002 election are clear.

“I’m not going to be part of any organization that tries to bring back an 80-year-old woman to be its president. If it’s in that bad of shape, maybe it deserves to…” as his voice trails off in resignation.

The 2002 election was quite an affair. Voting monitors, in signed statements to the NAACP Tri-State Conference of branches, said they witnessed new, non-English speaking members being coached on whom to vote for. The result of the election, Williams’ retention, also led to a protest petition by 27 members, including some from the Executive Committee, as well as a letter of protest filed by Henry. NAACP Special Committee on Internal Affairs Chairwoman Rose Gordon subsequently investigated that protest, submitted to Tri-State Conference President Edward L. Lewis Jr., to whom all NAACP branches in Idaho, Nevada and Utah report. The protest was found to be “frivolous and completely devoid of merit and the election results would not change, even if the matters alleged were assumed to be true.”

Phil Uipi, an attorney, real estate agent and activist in the Polynesian community, remembers enlisting members of his family and others to vote in the 2002 election. “Jeanetta asked me to see if I could help out,” Uipi said. “Jeanetta has been very good, maybe not specifically to the Polynesian community, but to the area as a whole … I’m not sorry that we did it, as Polynesians.”

Why Henry Really Lost

Although there was much controversy regarding that election, there may have been other, deeper reasons why Henry lost.

Bill Hesterley, a professor of management teaching organization theory at the University of Utah, wonders if the membership and even the community itself might, in fact, have been part of its own problem.

“Generally speaking, an organization’s membership will mobilize when they believe that they can make a difference or receive some personal benefits,” he says and compares that effort to cleaning up a community playground. “But the problem with that is it’s always better if someone else does it,” he says. “That way we receive all of the benefit with none of the cost.”

If everyone thinks that way, Hesterley describes the situation as “the collective action” problem. “Everyone is making the same calculation that someone else will do it.”

If Williams is guilty, as some claim, of being a poor leader, perhaps the community is guilty of being a poor constituency, which has possibly missed opportunities to take her leadership to task.

Indeed, a number of prominent black Salt Lakers were willing to talk in-depth about their frustrations with the Salt Lake Branch, but were unwilling to go on the record. Even state Rep. Duane Bourdeaux didn’t want most of our lengthy interview used for this article, but he made clear the tightrope he and other public servants must walk when dealing with delicate issues of civic concern.

“State government play a role in how organizations in the community can help improve the lives of others,” he said. “As someone who’s lived here and raised a family here, and now, as an elected official, I think there is a lot of room for improvement and I hope the key players reach out to the community. We haven’t reached out at the level we could and every day we’re losing opportunities. My goal is to be a bridge builder and to do my part to make state government, as a player with organizations like the NAACP, accountable and follow through on the larger goals.”

Ron Stallworth, an influential member of the Governor’s Office of Black Affairs’ Advisory Council, said, “The fact that I don’t have anything positive to say should speak volumes about how I feel about the organization. My momma once told me if you don’t have anything constructive to say, to not say anything at all.”

But the Rev. France Davis didn’t feel constrained to speak. He doesn’t think apathy surrounding the Salt Lake Branch is the problem. As pastor for Calvary Baptist Church, and a leader in the valley’s black community, he knows a thing or two about its sentiments.

“I don’t think the population is apathetic,” Davis says. Instead, he thinks the membership has focused more on the recruitment of organizations and less on people.

“And, as a result,” he says, “The people don’t have a whole lot of voice. One of the rules currently applied to people who make requests of the NAACP is ‘Are you a member?’ If you’re not,” says Davis, “there’s not much you can expect in return.”

When it comes to questions of how the Salt Lake Branch functions, he’s about as blunt as a reverend can be, and still be a reverend. “I hear constantly from people about their frustrations about not being able to get their needs met, not getting a response to requests for help with their problems regarding discrimination and other issues. There’s been a de-emphasis of organizational pursuits,” he says.

However, Davis also blames the Salt Lake City religious community, in part, for some perceived dysfunction at the NAACP. “The leaders of the religious community aren’t always working with each other to achieve the goals,” he says. “We need ourselves to get together to sit down and say, ‘Here’s what we believe is in the interest of the people, and here is how we need to pursue it.’

“I’d like to see the organization actively meetings the needs of the people in the community, answering their requests for help with problems on the job and in the workplace.”

Neither does Oswald Balfour think the community is apathetic, but for different reasons. A successful entrepreneur in Salt Lake City, Balfour says he “knows Ed [Lewis] and Jeanetta quite well,” but that doesn’t stop him from leveling a businessman’s eye at what he sees as the problem.

“Perhaps there were those who wanted to unseat her because she has served long enough and there’s a time to change, and I think in positions like that it’s good to have new people rotate in and out so you’re not developing a dynasty situation.”

Balfour also thinks the Salt Lake Branch doesn’t take advantage of a level of help that could make it effective, both in the community’s streets and its boardrooms. “What I find is that people moved here and they tried to get involved.”

But, he says, they run up against “the establishment.” He says, “People want to serve their community, but if they have to do battle just to do that, they say, ‘I’m not going to be out there beating my head just to serve,’ and that is what I find when people back off.”

- Durable, but controversial: NAACP Salt Lake Branch President Jeanetta Williams

See It My Way

The voice of Jeanetta Williams has served the community well. In 1998, her office was made aware of a Salt Lake City barber with a racially offensive message on his answering machine. He was subsequently forced to close his doors after the message was found to violate anti-discrimination statutes. She has raised issues regarding the discriminatory zoning practices in Bluffdale and Fruit Heights, was instrumental in creating the Multi-Ethnic Business Committee, and worked to make Utah’s elected officials more sensitive to the needs of their minority community.

However, in other cases, Williams’ leadership style has resulted in friction. There is evidence that she can be overly insistent to a fault, and she isn’t slow to complain about anyone who may slight her position. The most glaring example is the branch’s tumultuous relationship with the Governor’s Office of Black Affairs.

It may have started with comments by office head Bonnie Dew in an Oct. 25, 2002, Salt Lake Tribune article regarding Henry’s challenge to Williams’ leadership. Dew stated that she respected Henry “as a sojourner and would very much look forward to working with her.”

Dew also acknowledged a divide in the black community’s opinion of the Salt Lake Branch. “There’s definitely a rift in the community over the leadership of the NAACP,” Dew said. “But we as a community should get together and talk about it.”

NAACP Tri-State Conference President Lewis took umbrage, penning a vociferous Nov. 22, 2002, op-ed in the Deseret News accusing Dew of interfering “in the internal affairs of the NAACP.”

Matters between the Salt Lake Branch and the OBA grew further strained after Dew was invited to participate in a KSL 1160 radio show addressing the needs of Salt Lake City’s black community, then asked to leave. Listening to Lewis’ and Williams’ comments from her car radio after leaving, Dew was shocked at what she described as their biased comments against her office.

But if Dew was upset at Lewis’ and Williams’ comments about her office, Williams fumed at Dew for not sending her Black Advisory Council meeting minutes and financial statements from the OBA in a timely manner. Williams wrote the governor: “I have come to the conclusion that the NAACP cannot work with your Director of Black Affairs,” Williams told then-Gov. Leavitt.

Dew has declined comment regarding the NAACP Salt Lake Branch since 2002. Aside from the branch’s relationship with others in similar advocacy roles, there’s the question of how well it serves the minority community. Some allege the question of what you can do for the NAACP is often of greater importance than what the NAACP can do for you. Membership, they say, counts.

When Holly FieFia quit her job of eight years at a local grocery chain in 1997, alleging that her hourly wage was cut due to a manager’s racial bias, she filed a complaint with the Utah Labor Commission and phoned the NAACP’s Salt Lake Branch.

“I talked to Ed [Lewis] and I told him what my problem was, and he says first, ‘Are you a member?’ I said, ‘No,’ and he told me I need to become a member, and afterwards he’d send me the paperwork. He said, ‘Fill out the paperwork in detail and we’ll get back with you.'”

FieFia became a member, she said, and sent the branch some information about her complaint. She also sent Williams a letter, she said, and later asked Williams about the progress of her case when the two met at church. Williams told FieFia the information regarding her case was turned over to a lawyer, and that she would update her regarding any progress, FieFia said.

“I called and followed up one other time and never heard anything else from them, and that’s what happened with the NAACP,” FieFia said.

“If you have a complaint and you want to be heard and the NAACP is supposed to represent you, they should contact you through letter or through a telephone call. My only contact with Jeanetta was through church. When I sent my information and my check, I never got a call from either of them [Lewis or Williams],” FieFia said.

Lewis said FieFia might have misunderstood how complaints are to be filed. As Tri-State Conference Chair, he cannot oversee complaints, which must be filed at the local branch. He adamantly denies he would ever tell someone membership is required before they can get help. “I have never, and would never, make that statement to anyone,” he said.

Helen Fleming, a retired government worker, recalls how, per the recommendation of her pastor, she once phoned the Salt Lake Branch with a complaint of job discrimination. Williams asked her if she was a member, she says. Fleming wasn’t, so Williams mailed her an application. Fleming says she never heard back. But that didn’t discourage her from contacting the Salt Lake Branch with other issues. Nor, says Fleming, did it stop Williams from asking her, once more, whether or not she was a member. “I said I got out of the NAACP because, to me, it wasn’t doing anything to help the people,” Fleming says. “It’s not helping us at all. We don’t have any voice; we don’t have anything. It’s weak. And [Williams] said, well, since you’re no longer a member, you have to be a member before we can do anything to help you.”

When she served as a first vice president of the Salt Lake Branch, Charlotte Starks said that people frequently came to her with concerns. “People who knew I worked with the NAACP called me because, when they call Jeanetta, she doesn’t respond. I can’t tell you how many people have called me for help.”

As the losing challenger to Williams in the last NAACP election this Nov. 1, it goes without saying that Larry Houston had issues with Williams’ leadership. He had issues with the Salt Lake Branch even before he ran to lead it—and, he’s a member. “Over the last five years, I’ve asked for an independent audit to be performed and it’s never happened,” he says. “I think there is an accountability issue when members can’t get a true accounting.”

Williams takes these accounts one at a time. Many frustrations come down to the simple fact that people may not be familiar with how the NAACP is required to operate, she said. Preeminently, she challenges any allegation that people are told their complaints will get a hearing with the Salt Lake Branch only, and if, they’re a member. “Anyone who says that, I’ll tell them to their face that that’s a blatant lie,” Williams said. “I never tell people that if they’re not a member they can’t be helped. Some people will hear what they want to hear, and believe what they want to believe.”

Williams cites a recent incident involving a black military officer passing through the Salt Lake City International Airport who was not a member of any NAACP branch, local or national. After an altercation with a transportation official, he was arrested for disturbing the peace. But Williams says she addressed his case directly, and after phone calls to a state attorney was able to secure his release.

Williams doesn’t recall the particulars of FieFia’s case, but said that, regardless, church isn’t the place or time to bring up NAACP matters. Instead, people are free to bring up their concerns at the branch’s monthly membership meetings.

“There are a lot of people not involved who don’t come to meetings who want to throw stones all the time,” Williams said. “When people don’t know the requirements under which we operate they make assumptions to make the NAACP look bad.”

Williams doesn’t recall Fleming ever presenting the Salt Lake Branch with a complaint. But, once again, misunderstandings about proper procedure are common, which is perhaps why Starks had people come to her after they’d gone to Williams.

There are instances, Williams said, in which people with complaints expect immediate responses. This can be difficult when complaints must be put in writing and mailed. “We have to have everything in writing,” Williams said. “I’m not going to sit on the phone for people to tell me their whole stories.”

Williams almost breezily dismisses Houston’s charges. She feels he’s been disruptive at recent branch meetings. As for audits, the branch issues treasury reports monthly, which detail expenses and deposits, available to members. “It’s open, and there’s nothing secretive about it,” Williams said.

The branch doesn’t offer legal advice, says Williams, because it doesn’t want to be legally accountable.

As Tri-State Conference president, Lewis often acts as Williams’ spokesperson. Indeed, he often articulates policies for the branch on her behalf, noting that, “Since I oversee the operations of the Tri-State Branch, I also oversee operations at this branch.”

At more than 6 feet tall, he’s a striking man, impeccably dressed and articulate. He carries himself as every inch the executive. He’s also compelling—even demanding. When it was mentioned that background information about the branch had been obtained from conversations with past and present NAACP members, Lewis nearly demanded their names so that he might, “educate them on the policies and procedures of the Salt Lake Branch of the NAACP.”

Houston says both Lewis and Williams keep a tight rein on their decision-making powers. “Ed and Jeanetta don’t want to relinquish power and decision making. The committees are just figureheads.”

Another untruth, Williams said. “People who chair our committees have real duties and real jobs,” she said.

But the branch’s seeming reliance on rules and procedures remains a sore spot with some. Balfour, a man who says he understands the value of good PR, said he was undone by the branch’s lack of transparency. “For an organization as old and historic as the NAACP to say only insiders have an idea of how it works is really an indictment on the organization. Everybody should know,” he said. “It’s the NAACP!”

Who You Callin’ a Member?

“Membership is the lifeblood of the NAACP.” That’s the catchphrase you see on much of the organization’s promotional literature.

As a tax-exempt, nonprofit organization under section 501(c)4 of the Internal Revenue Code, the organization is eligible to receive contributions deductible as charitable donations for federal income tax purposes. But even though it receives tax-exempt status, it is not an open organization. Its records are not subject to public inspection, but this is true, in part, because it can’t afford them to be. Alabama tried to force the NAACP to disclose its membership lists in 1956. Such a disclosure could have harmed the individuals and businesses that believed in its mission but didn’t want that support publicly known. Because it’s an essentially private, members’ only organization, it’s not compelled to share information about planning, membership, finances or operations. It really can’t be compelled to do anything it doesn’t want to do.

Today, in 2004, concerns of a backlash are less prominent. Kevin Grimmett, chief financial officer for the Salt Lake City United Way, points out that a nonprofit needs to promote transparency. “Nonprofit organizations are corporations according to the state of Utah,” he says. “Most respectable organizations would be more than willing to disclose policies.”

Still, the NAACP needs new members, which must present it with a conundrum. New members come from the community. If the community doesn’t understand that the NAACP is an essentially members’ only organization, it might think it’s available to answer any question and address any need. The general consensus about the NAACP is that it’s not an exclusive organization. It has been historically regarded as an advocate that helps anyone, without preconditions. Some would argue whether that’s still the case.

Membership numbers are important, but those have been declining. In 1996, the National NAACP in Baltimore reported a total membership of 650,000. By 2004, that number was down to half a million, or a drop of 23 percent.

At a June 2004 luncheon for Life Members hosted by the Salt Lake Branch, that change in membership rolls was the elephant in the room. Billed as an appreciation, the luncheon emphasized membership recruitment. Lewis spoke on one of 10 initiatives, namely membership goals, set for branches by the national office in a five-year strategic plan that seeks to increase membership by 80 percent starting from 2001.

In step with the national organization, there’s also an elevated focus on revenue. In the years before Chairman Julian Bond and President Kweisi Mfume took the helm nationally, the organization was suffering both from a decline in membership and revenue. As part of an aggressive revitalization campaign, it seemed to shift its focus from community to corporate with the assumption that it is through business and access to business that the organization can best help people of color. Although membership numbers have continued to fall, the increase in financial strength of the organization has been phenomenal. According to a 2003 Washington Times report, the National NAACP operated in 2001 with a $40 million budget, a 135 percent increase from 1998, when the group reported revenues at $17 million.

Locally, the number of corporations that are paid and paying Life Members of the Salt Lake Branch of the NAACP jumped from 22 in 1998 to 27 in 2003, representing a 23 percent increase in five years and a 100 percent increase since 1993, according to Starks. In addition, the branch has between 500 and 600 general members and approximately 100 subscribing life members. Forty percent of all membership dues go to the branch. The remaining 60 percent go to the national headquarters in Baltimore.

The increase in corporate sponsors in recent years makes the financial fortunes of the Salt Lake Branch seem viable. Under the IRS category of a Civic League and Social Welfare Organization, the branch isn’t organized for profit and can only promote social welfare. It also means, generally speaking, there is no tax benefit to either an individual or corporation contributing money to the branch. Although a partial accounting of its finances was available, a full accounting was not.

Does Money Talk?

“Our corporate members do not exert any undue influence on our organization,” Williams volunteered when the subject of corporate contributors came up.

Indeed, the perception of undue influence by any outside entity on an advocacy organization can harm its reputation and its ability to recruit new blood.

Back at the U, Hesterley agrees it’s not much of a stretch to think that if a corporate entity co-sponsors a nonprofit with a purported role as a watchdog, it could become less of a watchdog if it fears jeopardizing outside money.

But Rev. Davis praises the branch’s relationship with corporations funding NAACP scholarships—to a point. “I’ve seen good and positive results in the area of scholarships being provided by business and funded by the various relationships with business,” he said.

He’s an advocate of outside involvement. But he also sees more scholarships being funded by corporate sponsors and less funded by the NAACP. Thus, he’s become aware of a feeling in the community that individual and community needs have been put on the back shelf in place of corporate courtship. He also sees a hidden, possible danger in relying too much on corporations.

“You can’t just expect organizations to support you financially, and then you turn your head when they are doing things to people they ought not to be doing,” says Davis. “I’d like to see the NAACP keep businesses honest, fair and doing justice on behalf of the people.”

I Do Solemnly Swear

And now this tale has come full circle. Williams won re-election for the Salt Lake Branch presidency Nov. 1, and by a wide margin. Challenger Larry Houston received 14 votes to Williams’ 63, with three votes contested. A closer look at the numbers proves instructive.

Those 80 officially registered voters constituted approximately 13 percent of the total branch membership, a total membership weighted heavily by an NAACP policy of providing up to 10 general memberships each time a corporate member purchases a table at a fundraising event. The branch hosts at least two major fundraising events each year.

In earlier times of the NAACP, corporate citizens routinely distributed those memberships to poor citizens unable to purchase their own. This ensured that historically disenfranchised community members could participate in the advocacy of their advocate. According to a decidedly ungrudgeful Mr. Houston, today that’s more likely to mean that a high percentage of general members are employees of the corporate sponsors, or otherwise strategically selected. How many of those voters participated in the Nov. 1 election is unknown. What is known is that in attendance at that vote was the cream of Salt Lake City’s legal and political crop. And such constituents often support the candidate with whom they have faith, or relationships.

During the Nov. 1 election night for the NAACP’s Salt Lake Branch, I sat in the second floor lobby of the Utah State Bar Law and Justice Center, where it was held. Between the election’s beginning and election’s close, I counted voters from a variety of ethnicities. Unofficially, I tallied 33 whites, 32 blacks, 10 Polynesians and another five voters representing Native, Asian and Hispanic Americans. In this respect, Williams is right when she states on the Salt Lake Branch website that the NAACP focuses on the needs of all ethnic groups, not just blacks. But it becomes problematic when, in the same website statement, that the NAACP “can’t be everything to everybody but we fight for the rights of all people.”

Williams is proud of her branch’s diversity as a “civil rights organization, not just for African Americans.” The intent is noble, but it must be asked how one organization formed to protect the rights of one specific group can successfully fight for groups with whom it shares no cultural history. Throughout my interviews, past and present members were torn over how the organization could do both effectively, especially when many felt the NAACP was “ours.”

Unlike the NAACP, other ethnic groups have chosen to stay in its mold, but not its shadow. For example, the National Association for the Advancement of Hispanic People (NAAHP) was formed in 2001 to promote advancement of Hispanics in America. Strengthening its base made more sense than broadening it.

The bottom line, however, is that Williams won re-election. Subsequent discussion of her legitimacy is academic. This election had not nearly the controversy of the 2002 branch president election, and was a relatively smooth one. Officers went to exceptional lengths to ensure that each and every parliamentary rule was precisely followed. On one hand, this guaranteed a minimum of disputes. But, says Houston, such exactness is a double-edged sword. Today, the Salt Lake Branch holds its executive committee meetings separate from its general membership meetings, a recent practice some believe contributes to miscommunications. Voting in a Salt Lake Branch election can be a bureaucratic experience. You must be a registered member 30 days prior to the election. You must have your card with you to vote. The procedures and bylaws can grow thick with requirements.

Houston compares the spirit of these requirements to America’s Jim Crow days, when government twisted laws so that it became impossible for the common person to know when and how to participate in government. “When you use those rules as a shield to keep someone from getting access or determine how they participate, you give the perception that you’re hiding something,” he said. “You can interpret rules to your benefit, as well as to enhance the community.”

Pointing to the branch’s August newsletter, Houston finds requirement information for anyone wishing to nominate committee members, as well as information about the Nov. 1 elections of office and committee members. But he said the newsletter contains no mention of membership requirements for those wishing to vote Nov. 1.

When asked initially, Williams said the August newsletter sent to branch members before the Nov. 1 election informed people that they must register for membership 30 days in advance of the election. When asked to point that information out, however, she then said she was mistaken. That information was not included. However, the newsletter contains all voting information required for publication by the national headquarters. She highlighted its contents. “People who read over it will see all that we do, and that there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Like Williams, Lewis is a stickler for rules. “I don’t get irritated very often, but when people make accusations about how the NAACP is supposed to operate without understanding the rules under which we operate, that’s one of the things that irritates me,” he said.

Best of All Possible Worlds

Many in the community see room for improvement in the Salt Lake branch of the NAACP. If everything could be hoped for, what would those improvements look like?

In a state with one of the smallest minority populations in the nation, Rev. Davis sees an even greater need for a vibrant NAACP branch. When people of color are scattered, they tend to face more problems than as a group. That’s when the need for an organization like the NAACP kicks in.

Williams didn’t pause long in answer to why some in the community see her as a polarizing figure, or take issue with her leadership style. “I think part of it is that I go by the NAACP book. I know what we’re supposed to do, and what we’re not mandated to do, and I don’t step outside of that,” she said. “People know I’m a stickler for abiding by the rules. I know what the NAACP rules are, and we need to abide by the rules.”

She works sometimes five or six hours on NAACP matters after her day job, sometimes even Saturdays and Sundays. That’s proof of dedication. Like Lewis, hers is an unpaid, volunteer position. And Lewis himself praises Williams’ branch as “one of the better performing branches in the tri-state area.”

Houston knows he criticizes the organization only because he loves it. “I think there is a greater need today for the NAACP. People of color are making more money and have more salary base than ever before, but we don’t have economic stability,” he says. “With all the negative things I’ve said I hope I’ve never in any sense downplayed what I think is one of the greatest organizations in American history for helping enforce values addressed in the U.S. Constitution, but,” he continues, “there’s always times people are in office too long, and they become stale and lose the vision because they’ve become entrenched in what they’ve done.”