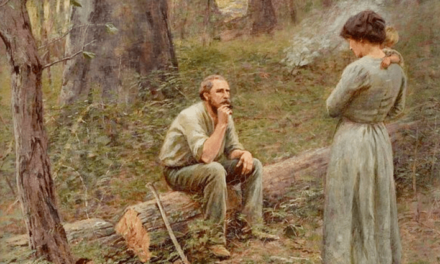

Martin Luther King Jr., Pete Seeger, Charis Horton, Rosa Parks and Ralph Abernathy at Highlander Folk School in 1957.

By David Winship

The Cumberland ridge of middle Tennessee may seem to be a far cry from the struggles on the streets of Mongomery, Alabama, in the 1950s. Yet there were direct connections and, were it not for the activity and education that came from the Highlander Center, the actions of Rosa Parks, the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the non-violent foundations of the Civil Rights Movement might not have been. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of many civil rights leaders who trained at Highlander, along with Rosa Parks, Ralph Abernathy, John Lewis, Septima Clark and Dorothy Cotton.

The Highlander Folk School located in Monteagle, Tennessee, was founded in 1932, modeled on the Danish Folk School which had an important role in revitalizing Danish culture and addressing the country’s social and economic problems in the late 1800s. Founder Myles Horton believed that such an educational institution, where both Black and white students and teachers could work together, could help address the problems faced by the American South and Jim Crow politics.

When Highlander was first established, it focused on labor education and organizing unemployed and working people. By the late 1930s, Highlander was training union organizers and leaders in 11 Southern states. During this time, Highlander faced and confronted segregation and racism in the labor movement. The first integrated workshops were held in 1944. The staff believed that “conquering meanness, prejudice, and tradition” in the form of racism and segregation was a key to overcoming poverty and initiating progressive change throughout the South.”

Highlander’s commitment to ending segregation made it a vital incubator and training ground for the Civil Rights Movement. Important civil rights actions, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Citizen Schools, and the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, all had ties in the training of the leaders of these programs who attended workshops at Highlander.

Among the programs that grew from the Highlander training programs was the Citizenship Schools, led by Septima Clark and Dorothy Cotton. These schools for adult, illiterate Blacks aimed to counter the voting rights barriers of the poll tests. The programs taught African Americans their rights, along with basic literacy skills. Recognizing how leaders developed during the Highlander training, Horton concluded that “educational work during social movement periods provide the best opportunity for multiplying democratic leadership.”

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) took over the Citizenship School program in 1961, according to Dr. King, “to fill the need for developing new leadership as teachers and supervisors and providing the broad educational base for the population at large.” The Citizenship Schools eventually trained 100,000 adults.

Among its other contributions to the Civil Right Movement was the development and establishment of the song “We Shall Overcome” as a primary civil rights anthem. Brought to Highlander as an old spiritual from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, the song developed through the sing-alongs which were a primary part of socializing at Highlander. The musical guidance of Zilphia Horton, Guy and Candy Carawan, and Pete Seeger helped establish its presence in the Civil Rights Movement.

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. returned to speak at the 25th anniversary celebration, he praised Highlander for its “noble purpose and creative work,” and contribution to educating “some of its most responsible leaders in this great period of transition.” Following the attention given to his speech, the Southern press attacked King and Highlander, leading to a revocation of its charter.

Pivoting to re-establish itself, Highlander continued as Highlander Research and Education Center, moving first to Knoxville, Tennessee, and then to New Market, Tennessee, to continue its work. In the 1960s and 1970s, Highlander focused on worker health and safety in the coalfields of Appalachia. Highlander played an important role in the emergence of the region’s environmental justice movement. During the 1980s and 1990s, its emphases broadened to embrace global environmental issues, while continuing grassroots leadership development. Currently, Highlander’s focus includes democratic participation and economic justice, immigrant and refugee rights, and contributing to intersectionality with other social movements.

In a memoir recollection, John Lewis revealed that it was at Highlander that he had his first meal in an integrated setting. “I was a young adult, but I had never eaten a meal in the company of Black and white diners … Highlander was the place that Rosa Parks witnessed a demonstration of equality that helped inspire her to keep her seat on a Montgomery bus, just a few weeks after her first visit. She saw Septima Clark, a legendary Black educator, teaching side by side with (Highlander founder Myles) Horton. For her it was revolutionary. She had never seen an integrated team of equals working together, and it inspired her.”

David Winship is a retired public school educator living in Bristol, Tennessee. He has worked with peace action groups in Southwest Virginia and creates programs for their MLK Commemorative events. He is a member of Winston-Salem Writers.