For a generation, America’s working class, as well as much of its middle class, lost political power. Rather than build their appeal on class interests, politicians kowtowed to Wall Street, Big Tech elites, university ‘experts’ and identitarian interest groups. But, as the 2024 presidential election clearly showed, the working class still has the clout to decide who gets put into the White House. Their choice of Donald Trump was a slap in the face to the ruling class.

The shift of working-class voters to the right, particularly those who work with their hands, has been developing for almost half a century. It accelerated during the pandemic, when their work largely kept the country functioning.

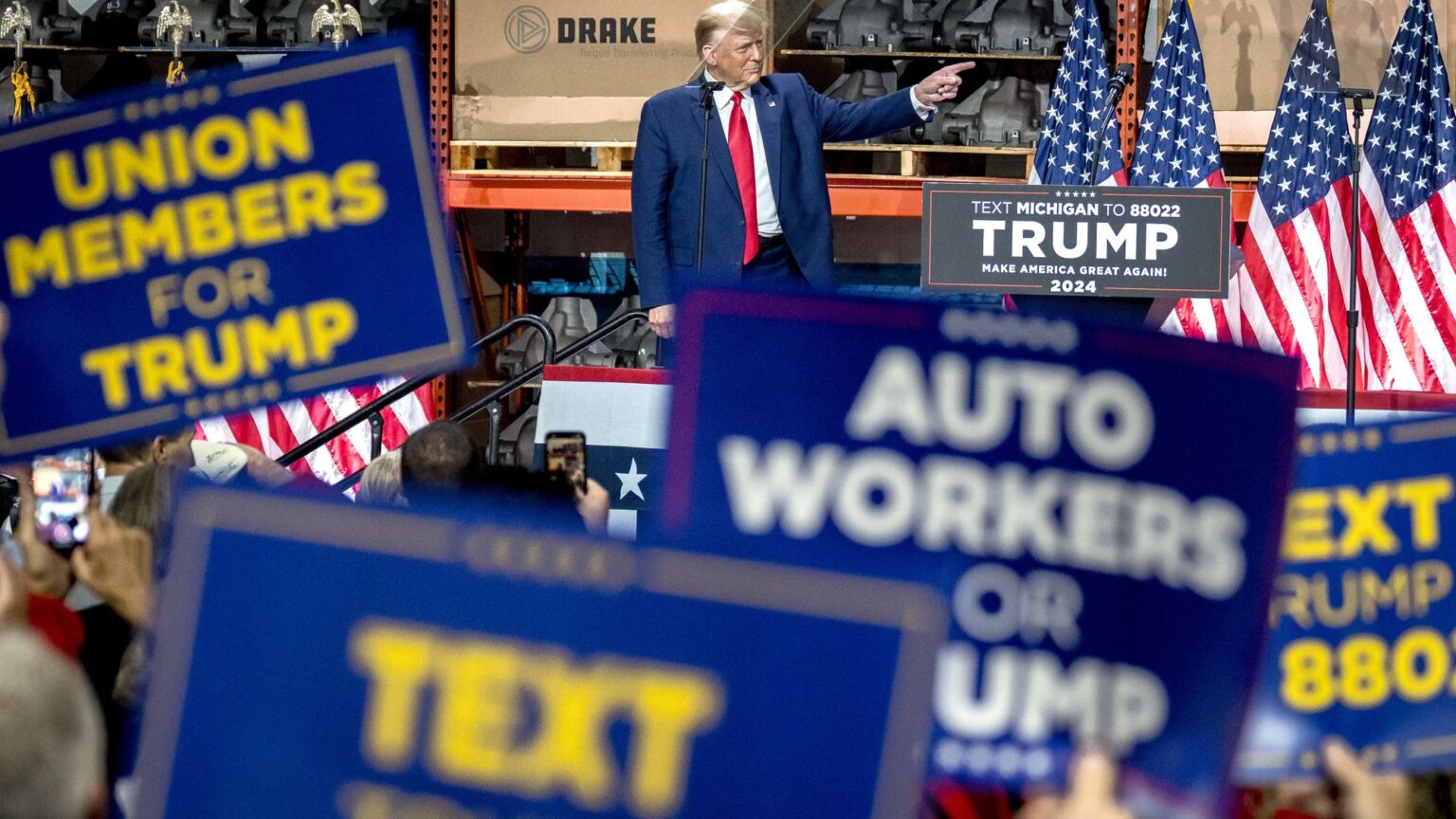

Although the number of college-educated voters has expanded, at least until recently, those without degrees still constitute around 60 per cent of the electorate. These are the voters most responsible for electing Trump, the first Republican nominee ever to win among low-income voters. In 2024, he won among non-college voters by 13 points. He even won over 44 per cent of union households, a proportion not won since former trade-unionist Ronald Reagan did so in the 1980s.

Perhaps most important in the long run, Trump also did well among Latinos, winning upwards of 40 per cent of their vote as a whole, and a majority of males. Many working-class Latinos preferred the immigrant-bashing Trump, because they are the ones who compete with and live in the same neighbourhoods as illegal migrants. His support won him formerly Democratic strongholds, from Texas’s Rio Grande Valley to California’s largely Latino interior. He also made major gains among African American males.

This working-class discontent is not unique to America. Similar patterns can also be seen in the UK, Germany, France and the Netherlands. Immigration has become a primary concern among these voters across the EU as well as Canada. According to Gallup, the percentage of Americans who wish to reduce immigration has soared. Roughly 60 per cent of Americans and a majority of Latinos support even ‘mass deportations’. Much the same shift of opinion has occurred in Europe.

Clearly, the party bases are shifting. As the corporate superstructure has moved to the Democrats, the GOP draws increasingly from small businesspeople, artisans and skilled workers. These voters never had much time for traditional Republican corporatism but felt abandoned by both parties.

Trade has been another central issue. Both parties have long embraced free trade and celebrated the inclusion of China in the World Trade Organisation. The result has been catastrophic for working-class voters. From 2001 to 2018, China’s huge trade surplus destroyed over 3.7million US jobs, notes the left-wing Economic Policy Institute. Similar losses have been experienced in the UK and in Europe. Germany, until recently an industrial powerhouse, is now losing much of its industrial base, notably in chemicals and cars, including the vaunted Mittelstand of small and medium-sized businesses. Even Volkswagen, creaking under electric-vehicle mandates, is closing factories for the first time in its history.

Living standards across the de-industrialising West have dropped, particularly for the middle class. Europe has endured a decade of stagnation while America has fared little better. It’s hardly a surprise that working class and many middle-class people are now in open revolt against the parties that they once embraced.

The challenge for Trump, and more broadly for the GOP, will be to keep the allegiance of these voters, particularly as the professional class heads ever more to the ‘progressive’ side. Trump and whoever he listens to these days seem keenly aware of the importance of working- and middle-class ‘normies’. His choice as vice-president of JD Vance, himself a product of an economically disadvantaged background, turned out to be a good move.

Vance, if he was to succeed Trump, could prove the great consolidator of the new GOP. He and others who share his views have developed an intellectual and policy programme focussed primarily on working-class voters. Some of Trump’s early appointments echo this orientation, including his nominee for secretary of state, Marco Rubio, a longtime advocate of GOP ties to working-class voters. His other nominations, such as Robert F Kennedy Jr as head of Health and Human Services, and pro-union Oregon Republican Lori Chavez-DeRemer as labour secretary have stirred fury among both conservatives and traditional Republican backers in the business world.

Similarly, the nomination of former Democratic congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard for director of national intelligence terrifies the GOP’s neoconservative wing but appeals to the populist base. Her pro-military and anti-interventionist bent especially seems ideal for working-class voters, who tend to fight the wars and suffer from the elites’ mistakes, but also tend to be far more serious about patriotism than their wealthier, better-educated counterparts. Latinos, the increasingly critical swing vote, boast some of the highest rates of military service. They represent the fastest-growing population in the military, making up about 16 per cent of all those on active duty. The number of police who are Latino increased 82 per cent between 1997 and 2020.

Despite these signs, Trump may not prove to be quite the tribune of the people some assume. Despite his savvy exploitation of working-class resentments, Trump could prove more pliant to oligarchic interests – including his best buddy, Elon Musk – in such things as antitrust enforcement and tax policies. Indeed, he could look to consolidate support among more traditional market-centric conservatives as well as cultivated friends like Musk and Apple chief executive Tim Cook.

The Democrats’ problem, however, could be even more challenging. Particularly harmful has been the primacy of two groups – the oligarchs of Wall Street and Silicon Valley, and radical cultural warriors, whose views are widely disparaged among the general population. The oligarchs have become ever more central to the party finances, but have steered the party away from emphasising unionisation and income redistribution. Big Tech and Wall Street may support radical cultural views on gender, race and the environment, but they certainly do not want to see their party turned into a forum for real class conflict.

These oligarchs are less concerned about economic decline – largely because they are doing well – than they are about maintaining what the New Yorker describes as ‘climate leadership’. The greens flocked to Harris’s cause, and they will prove difficult to fend off. The green non-profits make up a wealthy and powerful lobby, constituting what author and journalist Robert Bryce calls ‘the anti-industry industry’. In 2021, the green lobby received well over four times as much as those advocating for the use of nuclear or fossil fuels.

Among Democrats, climate tends to take priority over tackling inflation or the lack of high-wage jobs, as does the obsession with culture-war issues like trans, reparations and race quotas. Any shift from these positions will be resisted by many Democrats, such as former Biden press secretary and MSNBC media figure Jen Psaki, who, against all evidence, thinks the Democratic embrace of the trans agenda did not hurt Harris. Democratic congressman Seth Moulton, who has taken on the transgender lobby by saying he would not like his daughters to compete with biological males, has already incited the wrath of ‘progressives’.

Many Democratic mucky-mucks still blame voters for not feeling the ‘joy’ of the Harris effort. They ignore or dismiss their concerns over rising crime, a flood of undocumented migrants as well as the price of eggs and housing.

This is not a way to win elections. A better course for Democrats would be to concentrate on economic issues. Late in the campaign, some, like Bernie Sanders, saw the writing on the wall and belatedly tried to push Harris to make this shift. But Sanders himself has contributed to the ‘progressive’ make-over of the Democrats, having recently embraced all the extreme memes of the college-educated left, notably on the border and climate.

But it’s far from all over for the Democrats. Particularly if the economy suffers, the prospects for Democratic populists could improve. Even Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, the fan favorite of the ultra-woke, has ditched her pronouns and seems to be focussing more on economic issues. The American Prospect, a loyal ally of Biden, has pointed out that successful Democratic candidates tend to stress economic over cultural issues, while the Nation, a reliable linchpin of leftist opinion, has urged the party to ditch its ‘resistance’ approach to combating Trumpism for something less performative.

Ultimately the best way forward for the Democrats includes losing the far left entirely while restraining the anti-populist instincts of the oligarchs. The party needs to return to being ‘the party of the people’, but the people as they are, not as college professors think they ought to be.

Such a shift would require new leadership, largely from red-state Democratic governors like Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania or Kentucky’s Andrew Beshear, or perhaps a surprising newcomer like New York congressman Ritchie Torres. Such leaders can redirect the party back to a more traditional line.

The key realisation, in both parties, is that the working class is not, as some may hope, going to disappear anytime soon. Economic trends could actually boost the status and power of working-class voters. Indeed, with the rise of artificial intelligence, it is largely the college educated who are likely to suffer from what economists refer to as ‘skills-biased technological change’.

AI is already gutting the Democratically oriented professional class. Tech firms like Salesforce, Meta, Amazon and Lyft have announced major cutbacks in their white-collar workforce, and have warned that these positions are unlikely ever to return. IBM has put its staff hiring on hold while assessing how many of these mid-level jobs can be replaced by AI. In part to finance its drive to AI, Google has recently laid off 12,000 workers, a number that is expected to grow to 30,000. The damage may be even greater at the grassroots level. Within months of AI’s emergence, freelance work in software declined markedly, along with pay. Even those with ‘creative jobs’ – actors, writers and journalists – could be threatened as creative workers find their identities and creations copied or simply used in derivative products.

Yet if prospects for actors, set designers, coders and analysts fall, demand for blue-collar workers, like plumbers, electricians and mechanics, seems robust. After all, we are a long way from having robots who can fix pipes, install electric panels or do construction work. As AI pioneer Rony Abovitz told me, the big winner in the coming years will be the ‘sophisticated, technically capable blue-collar worker’. Young people might do well to forget Joe Biden’s famous advice to ‘learn how to programme’, and learn a trade instead.

This suggests that the working class is likely to grow and that could help the GOP, particularly if Trump’s policies create more jobs in industry, logistics and construction. The working class across the West may be down, but it’s far from out. Rather than being consigned as a relic of the past, workers may find themselves increasingly in an enviable position. Gaining their support, as in the last century, will be critical to any party that wants to win future elections.

Joel Kotkin is a spiked columnist, a presidential Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University in Orange, California, and a senior research fellow at the University of Texas’ Civitas Institute.