This article has been edited since it first appeared online.

Equal access to health care for all Americans was not legally granted until 1965 — just 60 years ago. Until then, Black patients were often refused treatment by white doctors and hospitals, and bright Black students desiring to study medicine were denied.

An exhibit at the Black History Museum & Cultural Center of Virginia honors Black people in the commonwealth who defied the odds to provide quality health care for all. “A Prescription for Change: Black Voices Shaping Healthcare in Virginia,” runs through March 15 and highlights many of the pioneering practitioners who left an indelible mark.

“This groundbreaking exhibition takes visitors on a journey that chronicles individuals, organizations and hospitals from the 1700s to the present through powerful narratives, along with rare documents, photographs and artifacts,” says the exhibition’s creator and curator, Elvatrice Parker Belsches. A public historian, author and filmmaker, Belsches chronicles the experiences of Black Americans in Richmond and beyond; she holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology from Hampton University and a bachelor’s degree in pharmacy from the Medical College of Virginia/Virginia Commonwealth University.

Compelling stories abound, including that of Jensey Snow (sometimes spelled Gensey), a nurse who saved the lives of Black and white families alike during an epidemic that ravaged Petersburg in 1825. Her enslaver granted her freedom for her service, and she became known as Jane Minor. She went on to train other Black nurses and to purchase the freedom of several Black mothers and their children in the Petersburg area.

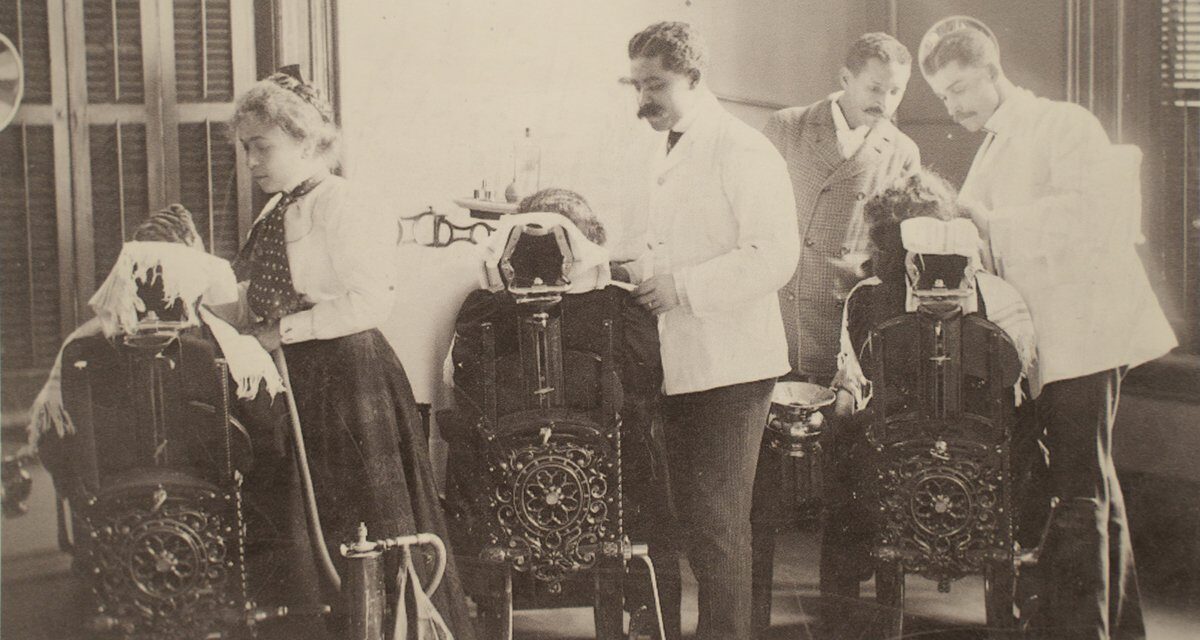

Then there’s Thomas Bayne, a dental apprentice known as Sam Nixon when he was enslaved by a white Norfolk dentist. He escaped via the Underground Railroad in the 1850s to Massachusetts, where he changed his name to Thomas Bayne. He practiced both dentistry and medicine there before returning to Norfolk after the end of the Civil War. Physician Dr. Alexander T. Augusta, born to free parents in Norfolk, went on to serve as one of over a dozen Black physicians commissioned as surgeons for the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. The list goes on.

“One of my favorite stories is about Peter Hawkins, the designated tooth puller for Richmond in the 1700s and early 1800s,” Belsches says. “According to Samuel Mordecai, the author of the 1856 publication ‘Richmond in By-gone Days,’ Hawkins made his rounds on horseback. Mordecai shared in his publication that Hawkins often extracted teeth without dismounting his horse!”

The exhibit also honors groundbreakers including Dr. John C. Ferguson MD, an 1875 graduate of the Detroit Medical College, who became one of the first Black physicians in Richmond and Virginia. Dr. John Meade Benson would become the first known Black person to pass the Virginia Board of Pharmacy licensure exam and be licensed as a pharmacist. Dentist Peter B. Ramsey became the first known Black dental school-trained dentist to be licensed in the commonwealth. Two dental instruments that reportedly belonged to Dr. Ramsey are on display in the exhibition.

The exhibition also features Dr. Sarah Garland Jones, one of Richmond’s most well-known trailblazers. Upon graduating from the medical school at Howard University in 1893, Jones successfully passed the Virginia Board of Medicine’s licensure examination and became both the first known Black woman to pass the medical boards here and also the first Virginia-born woman of any ethnicity to be licensed to practice medicine by the commonwealth of Virginia.

Until Howard University opened its medical school in Washington, D.C., in 1868, Black Americans who wanted to become health care practitioners had to travel hundreds or even thousands of miles to earn their degrees. Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, opened in around 1876 and the Leonard School of Medicine at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, opened in around 1882. By 1895, 385 Black doctors were practicing medicine in the United States; just 7% of them had obtained degrees from white medical schools outside the South. Today, the Howard University College of Medicine, Meharry Medical College, the Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, and the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Willowbrook, California, are the remaining HBCU medical schools.

“The Black Hospital Movement section chronicles the founding of health care institutions largely by Black practitioners around the commonwealth, who sought to increase health equity among the underserved communities,” Belsches says.

In 1902, Dr. Sarah G. Jones; her husband, Dr. Miles B. Jones; and several other Black medical practitioners established the Richmond Hospital and Training School for Nurses, which continues today as Bon Secours Richmond Community Hospital and the Sarah Garland Jones Center, a community wellness facility in the East End. In 1920, the Medical College of Virginia opened St. Philip Hospital, which is now part of Virginia Commonwealth University.

The “Prescription for Change” exhibit also includes the history of Black professional medical organizations founded by Black health care practitioners in medicine, dentistry, pharmacy and nursing. “In the South during the 1800s through the end of segregation, with few exceptions, the majority-white organizations in the segregated South didn’t extend memberships to Black practitioners, [so they] founded their own parallel organizations,” Belsches explains. “One of the earliest was the National Association of Colored Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists in 1895. It continues today as the National Medical Association. These organizations provided a profound sense of collectivism, fellowship and invaluable opportunities for continuing education. Each is currently open to all who are qualified.”

Dr. Paula Young, chief medical officer at Richmond Community Hospital, who is Black, encourages the public and her fellow practitioners to visit the museum. “The exhibit provides so much meaning to what we do,” she says. “It motivates me to do my best, knowing what people went through for me to have the ability to work where I work in the capacity that I do. I get the privilege of doing this at Richmond Community Hospital that has such historic presence and significance.”

Despite major strides, Young says, the industry still has work to do to level the playing field. According to a 2021 study by UCLA, fewer than 6% of doctors in America are Black and 3% are Black men — a number that has remained essentially unchanged since 1940. The VCU School of Medicine is working to move the needle. Its 2025 graduating class of medical students is the most diverse in the country.

Belsches hopes her exhibit will inspire Black students to pursue careers in medicine. “In all that I do, I seek to honor our elders and inspire our youth,” Belsches says. “If young people and elders alike can learn about these incredible practitioners who against the odds created hospitals, made medical discoveries and became national organizational leaders, then they’ll be reminded that, with faith and hard work, all things are possible.”

Never miss a Sunday Story: Sign up for the newsletter, and we’ll drop a fresh read into your inbox at the start of each week. To keep up with the latest posts, search for the hashtag #SundayStory on Facebook and Instagram.