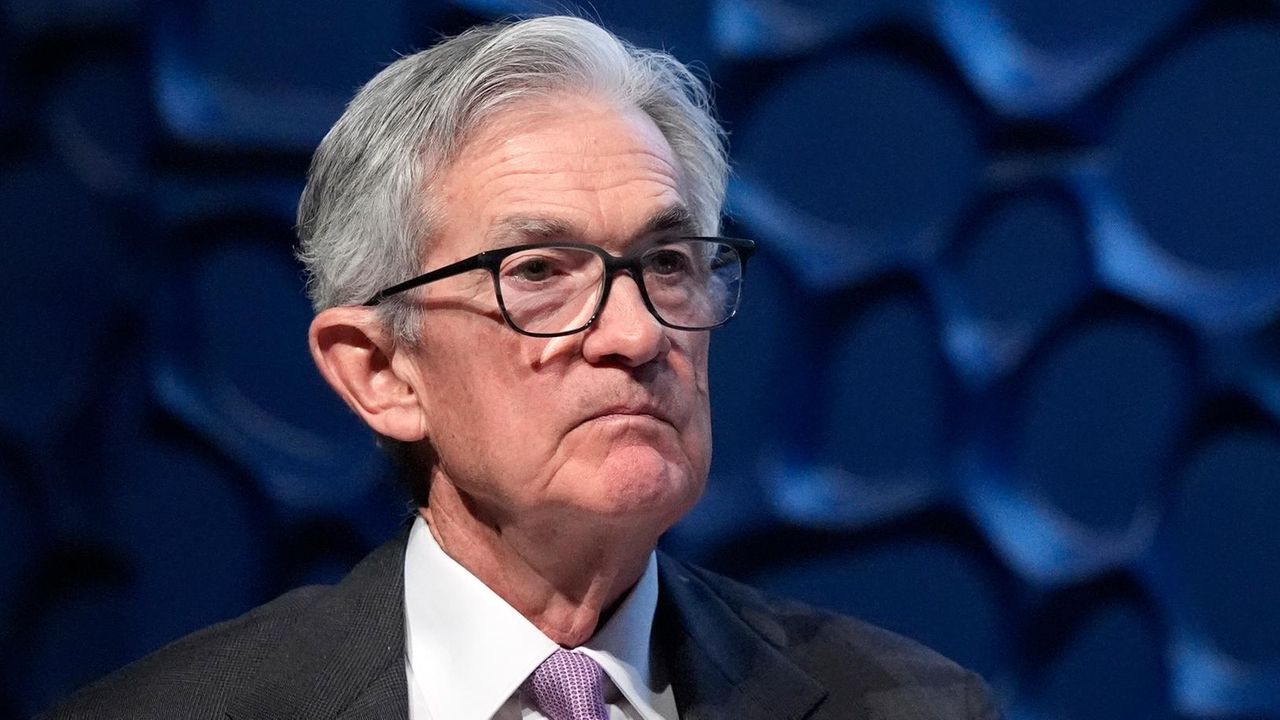

If U.S. economic growth is so good, then why does the Fed need to cut interest rates?

That was essentially the question put to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell recently after a speech in Dallas. It would be more constructive to examine the premise — why is growth so good? — and ask what the Fed and others can do to keep it that way.

Real GDP is on track to exceed its pre-pandemic trend for the second straight year. Typically, the Fed might worry that strong growth is a sign that the economy is in danger of overheating, but not this time. Inflation fell. The extra growth largely reflects higher productivity and a faster-growing workforce. Supply-driven growth is not inflationary; to the contrary, it can be crucial for rebalancing supply and demand and lowering inflation.

Underpinning the success is the growth in labor productivity, which has averaged 2.3% in the past two years, about half a percentage point faster than in the four years before the pandemic. While it may not sound like much, that difference would shave almost 10 years off the time it takes to double the level of real GDP. Except for a brief period in the 1990s, however, sustaining a higher pace has long been difficult.

Judging the sustainability of the current productivity uptick requires examining its roots. One encouraging sign is that the sizeable pickup in new business applications that started early in the pandemic is ongoing. Moreover, research shows that the applications led to new businesses with employees, especially in the innovation-heavy tech sector. After decades of a falling startup rate, since the pandemic the U.S. economy has slowly become more dynamic.

The initial burst of business formation early in the pandemic appears to have been a reaction to the large shifts in economic activity due to the public health emergency and a shift to remote work. Pandemic relief policies also appear to have had the unintended consequence of lowering the financial barriers to starting a business. In fact, there is evidence that stimulus payments and other income support boosted entrepreneurship. Areas with higher populations of Black Americans, often underrepresented among business owners, were particularly likely to see an increase in applications, suggesting how powerful it can be to lower barriers to entry.

The productivity pickup is not just about new, innovative firms. It’s also about workers moving to jobs that better match their skills. While disruptive, the so-called “Great Resignation” of 2021-22 allowed many workers to move to jobs that allowed them to be more productive. Researchers have pointed to the high churn of workers earlier in the pandemic as a key reason for the recent upturn in U.S. productivity. New business applications were also higher in industries and geographical areas with higher levels of job-quitting. A dynamic labor market is directly tied to a dynamic business environment.

But a few years of higher productivity is not enough. The question now is how to extend the gains. While another round of income support is unlikely, there are other ways to lower barriers to entry for new businesses.

The new administration has pledged to eliminate federal regulations across the board. It should focus on regulating judiciously — which could mean adding or subtracting from the existing code — in a way that supports competition and innovation. That would support startups, particularly in new areas like generative artificial intelligence. By concentrating on the issues facing small, young businesses — as opposed to large, well-established corporations with a lot of lobbyists — the administration could foster innovation and further recent trends in business formation.

The Fed, for its part, has to be careful not to restrict the economy too much. High interest rates can cause companies to invest less in technology , thus slowing productivity growth. In fact, in the two years since the Fed began raising rates, investments in venture capital have declined by almost half. Curbing growth when it is inflationary serves the Fed’s dual mandate, but curbing productivity growth does not — and puts longer-term growth at risk.

The cooling of the labor market, albeit gradual, is also a cause for concern. The rate of employees quitting jobs (often to move to a new opportunity) has fallen back to levels last seen in 2015, when productivity growth was notably slower. Moreover, the quits rate shows no signs of stabilizing.

It’s not the dramatic weakening common in a recession, but protecting the dynamism of the labor market should be a priority. The Fed correctly set “no further cooling” as its test for the labor market. The current strength in growth should reinforce that judgment.

For both the Fed and other policymakers, now is not the time for complacency. Watch the labor market and the rate of business formation: If they slip back and become less dynamic, then productivity and supply-driven growth could slip away, too. The U.S. economy has come too far in the last few years to allow that to happen.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners. Claudia Sahm is the chief economist at New Century Advisors and a former Federal Reserve economist. She is the creator of the Sahm rule, a recession indicator.