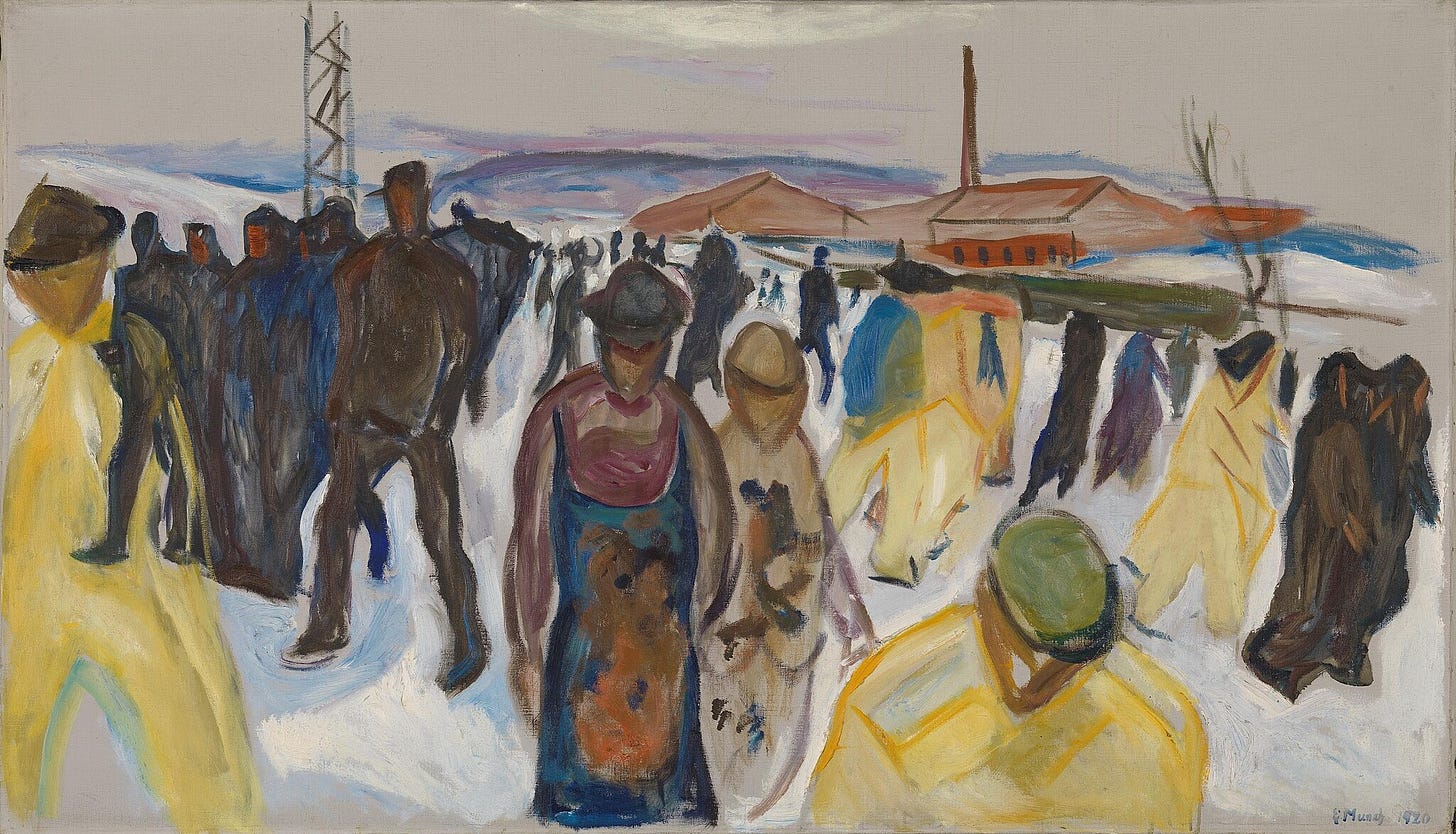

Left behind. The gap between ‘woke’ elites and poor or working-class Americans is wider and more salient than ever. Image Credit: Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944), “Workers Returning Home”/Wikimedia Commons

Left behind. The gap between ‘woke’ elites and poor or working-class Americans is wider and more salient than ever. Image Credit: Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944), “Workers Returning Home”/Wikimedia Commons

In this episode of the Pluralist Points podcast, Ben Klutsey, the executive director of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, speaks with Musa al-Gharbi, an assistant professor of journalism, communication and sociology at Stony Brook University, about his forthcoming book, “We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite.” They discuss the evolution of terms like “woke” and “politically correct,” how social justice beliefs can be both sincere and self-interested, why elites don’t always realize they’re elite and much more.

BENJAMIN KLUTSEY: Thank you for joining Pluralist Points. Today we are talking to Professor Musa al-Gharbi. He is the Daniel Bell Research Fellow at the Heterodox Academy. He is assistant professor of journalism, communication and sociology at Stony Brook University. He is an interdisciplinary scholar and public intellectual whose work covers race, inequality, social movements, extremism, policing, national security, foreign policy and domestic U.S. political contests. He covers really a wide range of things. His first book is “We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite,” which is the subject of our conversation today.

Musa, thanks for joining us.

MUSA AL-GHARBI: Thank you for having me.

KLUTSEY: Now let’s start a bit further back, before your academic career. What interesting insights did you learn about sociology selling shoes at Dillard’s?

AL-GHARBI: You do learn a lot doing these kinds of retail jobs. One thing that you learn how to do, that served me well later as a public intellectual, is that a lot of people think that when you’re selling shoes (or anything else), what you want to do is just try to cram as much stuff into the customers’ bags as possible. But that’s not actually what you necessarily want to do as a salesperson, because you don’t actually make a living as a salesperson—especially a commissioned salesperson (which is what I was)—through one-off sales.

You’re able to succeed and flourish as a salesperson by repeat customers, by getting people who are satisfied with the thing and they want to come back, and they want to come back to you specifically to meet their future needs. In order to do that, it’s really important that you have to listen and learn about what the customer actually wants and needs and connect the things, leverage the knowledge that you have about the different products, about what’s in your store, the specialized knowledge that you have, to meet their wants and needs effectively.

Maybe the thing that’s the best fit for their needs isn’t the thing that’s the most expensive or whatever. Maybe they won’t walk out with anything because they just happened to need something, and there’s actually somewhere else or some other thing that’s actually a better fit for what they need.

When you build that trust by just being honest with them and leveraging the specialized knowledge to meet their needs, when you listen to them and pay attention to what they actually want and need, then that’s how you succeed as a salesperson.

KLUTSEY: It applies to selling books as well.

AL-GHARBI: Yes, absolutely. This is one thing that served me well so far as a public intellectual, is being able to take the specialized knowledge that I have and communicate it to nonspecialists in a way that they find accessible and compelling, to speak to the things that they care about, which is part of why I talk about so many things in my research. But also—the general point is, that’s an example of a type of skill that I cultivated selling shoes that became useful to me as a fancy nerd as well.

Another thing that’s really striking about doing jobs like selling shoes as compared to being an intellectual—actually a thing I kind of miss, honestly—is that when you’re selling shoes, you spend all day helping people solve problems. They have real, actual problems. “My kids need to go to school. They need something on their feet.” Or “I’m starting to work out. I need shoes for this.” Or “I’m getting married. I need nice shoes that go with my dress.”

The problems you’re helping them solve are not usually life-changing. You’re not saving the world or anything like that, but people come in—but at the end of the day, when you punch out, you’ve spent your whole day helping people solve concrete problems, helping actual people solve concrete problems in the real world. And that’s not a feeling I basically ever have as an academic. [laughs]

I do kind of miss that, to be honest, despite the fact that, of course, in my current vantage point, I get paid a lot more. I have a lot more social prestige and all of this. But I do miss the feeling of just helping real people solve real problems in the real world every day.

KLUTSEY: Yes. So that’s actually something you and I have in common: I did sell shoes at one point in my life at Payless ShoeSource, many, many, many years ago. What you’re saying is certainly absolutely right. I think you do a lot, and you feel as though you’re helping someone in real time.

KLUTSEY: Now, back to the book and the title of the book: “We Have Never Been Woke.” You intentionally do not define “woke” in the book, but how would you describe it? Is it just social justice activism?

AL-GHARBI: Yes, so one of the things I emphasize in the book is that “woke” is a term that is subject to a lot of contestation. So rather than picking one side in this contestation, what I try to do is explain what different people seem to mean when they talk about “wokeness” or “being woke.”

I start by walking through the history of the term, walking through how there were other terms that seemed to serve a similar function in the discourse—like “political correctness” in the late ’80s to early ’90s. In fact, political correctness, as I argue, can be really illustrative for understanding the social tumult around “woke.”

“Political correctness” was a term that goes back to the ’50s. When people started using the term “politically correct,” they meant it to literally mean “my views are correct,” “my political views are correct,” “my moral and political views are correct.” To be “politically incorrect” at that time had a valence like saying someone was problematic. If someone was telling you, “Hey, you’re politically incorrect,” it’s like saying, “Hey, that’s a problematic thing you said.”

Over time, this use of “politically incorrect” by one faction within the left—the term came to have this different valence for another faction of the left, who started to associate political correctness with a sanctimony or a focus on symbolic gestures over addressing real problems and so on.

Eventually, this dispute within the left about what “political correctness” means got seized on by the political right. They basically started using the term “politically correct” to cudgel anyone who was left of center, anything vaguely left: “Oh, you want to raise taxes? That’s political correctness for you.” Everything was “PC” or “politically correct”—everything they didn’t like.

Eventually, it became difficult for anyone to identify as politically correct. After a point, no one said, “Oh, I’m PC” in any kind of proud way. Even the concept of being politically incorrect came to take on a somewhat positive valence. Even people were willfully politically incorrect, and that was edgy and stuff like this, right?

Eventually, people abandoned—they stopped talking about themselves this way. It was pretty much only people disparaging the left who continued to use the word “political correctness.” Eventually, then, people on the left searched for new—played around with different terms to replace that term, and eventually they settled on “woke.” But then the same kind of process played out. There’s this tension within the left about what “woke” means, what woke activists are doing. Then this was seized on by the right.

Now the term has become unpopular on the left, and basically no one today is standing up, like, “I’m woke. I’m woke and proud.” Except Kamala Harris, actually, like a year ago, was like, “Everyone should be woke. Woke is great.” She’s the exception to the rule, and actually I don’t think she would say that today as she’s running for president. But you see the same thing play out.

As I mentioned in the book (real quick), there are a couple of things that people on the left and the right do seem to agree on, if you were going to care about what you would characterize as woke or who you would characterize as woke versus who you wouldn’t.

For instance, one example that I talk about in the book is the idea of trans-inclusive feminism. Someone who was a feminist but wasn’t trans-inclusive, or someone who was not a feminist, would not be understood as woke in many circles on the left and wouldn’t be understood as woke on the right either. There are a few of these kinds of perspectives or modes of political engagement or thought that do seem to have a consensus, where most people across the political spectrum would describe that as woke, or would describe people who don’t do those things as definitely not woke. I tick through a few of those in the intro to the book as well.

KLUTSEY: Yes. And you also talk about—in the book, you cite a poll—a USA Today and Ipsos poll from 2023 that finds that although most Americans view the term “woke” positively in the abstract, a plurality of respondents said they would interpret it as an insult instead of a compliment if someone referred to them as woke. I guess in many ways it has lost its shine, if you will.

AL-GHARBI: Yes, absolutely. That polling really reflects the transition of the term being used primarily by people who actually identified with the term to describe themselves in positive ways, to being primarily used by people who don’t personally identify with the term to disparage other people they disagree with. Now, yes, people would not view it as a compliment if they were described as woke.

KLUTSEY: Yes. Symbolic capitalists use the term “woke” or would probably embrace a wokeness. Can you describe what “symbolic capitalism” is? In some ways, I guess it’s similar to having a social capital or perceived high status in society, but can you unpack that for us?

AL-GHARBI: Sure. The main characters of the book are a group of people who I call symbolic capitalists. They’ve been known by other names in the past. “The professional-managerial class,” for instance, is another popular name to refer to the same group of people. Basically, what the book emphasizes is that, starting in the period in between the world wars and then accelerating after the 1960s and into the 1970s, there were these shifts to the global order that favored people who work in what I call the symbolic professions, so who work in industries like consulting or the media and the arts or administration or journalism or education and so on and so forth. So, people who make a living by producing and manipulating symbols instead of providing physical goods and services to people.

People who work in these fields, basically, how they make a living, how they gain social status, how they—etc., it all comes down fundamentally to basically what you know, who you know and how you’re known. For this reason, I refer to the people who work in these professions as symbolic capitalists, here drawing on sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of symbolic capital.

Symbolic capital: what it is, on Bourdieu’s account, what symbolic capital is, is the way that people who are elites use—it’s a cultural resource that elites use to try to get other people to follow them.

He came up with three forms of symbolic capital in his books. One of them is academic capital. That’s when you try to get other people to listen to you by—in virtue of the credentials that you have or through your association with fancy institutions that are associated with knowledge production. So “I’m a professor at Stony Brook University,” or “I have a Ph.D. in sociology from Columbia, an Ivy League school.” So evoking my PhD or talking about how it’s from an Ivy League school or talking about how I’m a professor at an R1 research university like Stony Brook University, to the extent that I evoke these kinds of associations or these credentials and things like this, that’s me trying to get other people to listen to me based on the specialized knowledge that I have.

OK. Another form of symbolic capital that Bourdieu mentioned is called political capital. That’s when you get other people to listen to you because you have a reputation of being effective and of being honorable and of being—or because of the literal rank that you hold in an institution. “I’m the manager. You have to do what I say because I’m the manager.” These are all forms of what Bourdieu called political capital. That’s getting other people to listen to you because they trust you or because they feel like they have to based on the position that you have.

Then finally there’s what he called cultural capital, which is when you get other people to listen to you, to defer to you, to try to advance your goals or follow your plans because they like you or they want to impress you or because they think that you’re cool or interesting or sophisticated or, in some other way, being attractive.

One of the arguments of the book is that the modes of speaking and thinking about social justice issues that people often associate with wokeness—one of the main things that they do today is serve as a form of cultural capital. The people who master these ways of talking and these ways of thinking—one of the functions it serves is to show people that I’ve read the right books, I’ve gone to the right schools, I’m from the right kind of background.

So people who are less affluent, people who are poor, people who are less educated, they’re actually the Americans who are the least likely to hold these kinds of views or talk and think in these ways. Talking and thinking in these ways is a way of showing people your class position. It’s a way of showing people your elite background. It’s a way of showing people that you belong in elite spaces.

This is an irony. This is one irony of the way that social justice discourse functions in practice, regardless of people’s intentions or feelings or desires. In practice, one of the key functions that social justice discourse serves is to signal to people who’s part of the “in” crowd and who isn’t. And to justify, basically, excluding or marginalizing or punishing people who don’t say the right things or feel the right things or behave the right ways.

KLUTSEY: Yes. Now, in the age of populism, are symbolic capitalists still powerful? Do we still have any strength or any legitimacy in society?

AL-GHARBI: They are still powerful. A scholar that I worked with a lot when I was at Columbia, Gil Eyal, he has this book called “The Crisis of Expertise.” One of the main things that he shows in this book is that it’s increasingly the case today that so much of people’s lives is shaped by experts and expert knowledge.

Policymaking, for instance, even in Congress and stuff—a lot of the congresspeople aren’t themselves symbolic capitalists, but when they’re designing policies and implementing policies, they rely heavily on expert testimony and things like this. Judges rely on expert testimony when making rulings. The kinds of products that are associated with the symbolic economy govern people’s lives in deep and important ways—things like algorithmic curation, surveillance, data collection. All of these kinds of things profoundly shape people’s possibilities in many respects.

We are influential and we continue to be. In fact, our influence is growing even as our legitimacy is falling. Actually, this is one of the things that Eyal emphasizes, is that part of why there is so much contestation around expertise is precisely because it’s so important in the contemporary world, including for shaping politics. The way he puts it is, the growing scientization of politics has reinforced the politicization of science, so these two trends are related.

Then one thing that I show in the book, that I think is an important contribution to understanding some of the tumult we’ve seen around trust in institutions over the last 10 years and polarization around science and things like this, is that it’s generally the case that people who work in the symbolic professions have very different ways of viewing the social world than most other people. We have very different ways of engaging in politics than most other people; we have different kinds of political preferences. Those differences are always pretty big, even in normal times.

Then after 2010, symbolic capitalists shifted a lot. There was a period of what I call “great awokening,” where the ways that symbolic capitalists start talking and thinking about social justice issues, the ways that we participate in politics, shifted a lot really fast. Whereas—and most other people didn’t shift much at all. As a consequence of that, the gap between us and everyone else grew rapidly.

We tend to recognize that the gap between us and everyone else grew rapidly, but the story we tell ourselves about why that gap is growing is because those people must be radicalizing. When you actually pay attention to the charts, you can see that all the action is actually with us. We’re the ones who are radicalizing.

After 2010, this gap between us and everyone else grew—it grew bigger, and it also grew more salient. People were more aware of this gap and they cared about it more, in part because people like us, symbolic capitalists, became a lot more militant about confronting and denigrating and mocking and trying to purge people who didn’t think and say and feel the right things or engage and have the right kind of politics. We actually made the gap between us and everyone else more salient in everyone’s mind. They recognized it more; they cared about it more than they normally would.

As a consequence of that, that created an opening for other political actors, associated primarily with the Republican Party at present, to basically campaign on trying to bring people like us back under control, to restore these institutions to their rightful purpose, to check the power of these bureaucrats and academics who are out of control, to punish the media for its bias and so on and so forth. There’s this opportunity that was created for other political entrepreneurs to basically try to gain political power by campaigning on bringing us under control.

This is a situation that we ourselves created, both in terms of how dramatically we shifted over the last 10 years and how unfortunate some of our engagements with non-symbolic capitalists were over the last 10 years.

KLUTSEY: The militancy that you describe with which the symbolic capitalists advance their ideas and so on—it seems to me that it is a search for meaning, a search for virtue, because there is a lot of talk around justice and equality and courage to push back against the powers that be and so on and so forth. Do you sense that in your research, that this is a search for meaning and purpose that a lot of these people seek?

AL-GHARBI: Yes. There is some research that shows that, for instance, when you look at who’s most likely to subscribe to a lot of the views associated with wokeness, it does tend to be people who are of former White Anglo-Saxon Protestant background, basically, who—many of whom have left religion.

For a lot of people who either no longer are affiliated with a religious tradition per se, who are atheists or agnostics or spiritual-but-not-religious or anything in that vein, or for people who might identify as Christian but don’t go to religious services regularly or who aren’t actively taking part in religious traditions and religious communities—OK, for these people, it does seem that there is some evidence that political participation and engagement can be a way that they can feel like they’re part of something that’s bigger than themselves, that they’re engaging in this important transcendent movement, that they’re part of something that predated them and will continue beyond them. Some of the same kinds of impulses and satisfactions that people get from participating in religion. I think there’s definitely something to the …

In fact, one of the things that I think that drives some phenomena that we talk about, like cancel culture, is in part because there is this sense of helplessness that people sometimes feel when they think about problems like racialized inequality or abuses by police, where they feel helpless. Although I should add, this feeling of helplessness is itself not true. Frankly, it’s a lie that we sometimes tell ourselves to absolve ourselves of responsibilities for problems that we create.

Setting that aside, a lot of people feel this sense of helplessness where they don’t think that they can do anything about some of the social problems that they’re confronted with, but they do know they can definitely destroy this person who has come to represent that problem in some way.

You’ll see some white lady who has an awkward interaction with some Black youths that gets caught on tape. A lot of people who feel like they can’t do anything about racial injustice know that they can at least get this person fired from their job, that they can smear this person, damage this person, purge this person from our presence. Doing that does give them a sort of satisfaction that they’re doing something, even though it won’t get anyone released from jail, it won’t save anyone’s life, it won’t lift anyone out of poverty. It won’t do that, but they do get the sense that they’re doing something—and that feeling is, I think, a big thing that people are chasing.

AL-GHARBI: That said, people are also chasing their personal interests in various ways through a lot of the social justice posturing. Here I think it’s important—one thing that I think that the book tries to stress, and that I hope it can contribute to the conversation, is that a lot of times when people talk about people pursuing their interests by appealing to social justice goals or things like that, the assumption is, if they’re trying to pursue their interests through appeals to social justice, then they must be cynical. They must not actually believe the words that they’re saying. They must be just engaging in a game.

But I think—and there’s actually a lot of empirical research in the cognitive and behavioral sciences that underscores this point—that that’s a bad way to think about thinking. If we understand that our cognitive—or our brains, the ways that we perceive the world and think about the world are fundamentally oriented towards advancing our interests and furthering our goals rather than just perceiving things in some kind of objective way—which is what the balance of research today suggests, is that our cognitive perceptual systems are fundamentally geared towards advancing our own interests, furthering our goals.

If we run with that premise, one thing we might expect is that if there’s some belief that we could hold that advances our interests in some ways, we would actually become much more likely to believe that thing, to believe it fervently and sincerely and to try to get other people to believe it too.

There actually isn’t any contradiction between trying to advance your own goals and believing something sincerely. You would expect that it enhances sincerity, that if something is of interest for you, to believe and to advocate to others. So I have no doubt that most of the people who espouse social-justice-oriented beliefs sincerely believe—they really do want the oppressed to be liberated, they want the poor to be uplifted, they want people who are disadvantaged and marginalized to live lives of dignity and respect. I have no doubt about that. The problem is that that’s not their only sincere belief.

They also very sincerely want to be elites, and by that I mean they want other people to defer to them; they want other people to listen to them. They want to have more power and status than most people. They want to have a higher standard of living than most people. They want their own children to reproduce their own elite position and maybe do even better. These drives are in some fundamental tension, right? It’s tough to be an egalitarian social climber. [laughs] That’s kind of a nonsense label.

What ends up happening is that this drive to be an elite and this drive to be an egalitarian—people hold both of those beliefs sincerely, but when they come into conflict, which they often do, it’s typically the desire to be an elite that ends up dominating. And it ends up subverting, in some ways, the ways they try to pursue social justice.

AL-GHARBI: You see all of these people basically trying to pursue social justice, but in ways that don’t require any kind of change on their end, in terms of their own lives, in terms of their own aspirations, in terms of their own social standing. What they’re trying to do is achieve these goals by taking from others, and including and especially the focuses on the top 1% or the millionaires and the billionaires.

But as I explain in the book—I think one thing that comes through in the book, I hope, is that we actually can’t just solve a lot of these social problems by taxing Elon Musk more or Jeff Bezos more. There’s compelling cases that people can make that these folks should pay more taxes. But at the end of the day, as Richard Reeves shows in his book “Dream Hoarders” and a lot of other research shows as well, when you want to understand things like growing social inequality, economic stagnation, the lack of social mobility and things like this, you actually have to really look at the behaviors and lifestyles of the top 20% of Americans. It’s the top 20% of Americans that control 72% of all wealth in the United States today.

If you just look at the top 1%, they own a radically disproportionate share, but they own 27% only. If you just focus on the top 1%, though, you miss the vast majority of wealth and stuff in this country. It’s the top 20% you really have to look at. Another reason why you can’t just look at the top 1% is that even when you think about the millionaires and the billionaires and all the terrible things that they do, how do they accomplish those things? It’s mostly with and through us, right?

If you think about the ways that billionaires present themselves as the solutions to problems that they help create (which is the same thing that we do, by the way), but who helps them do this? It’s symbolic capitalists who are running their PR machines, who are helping launder their money in finance and so on and so forth.

People were criticizing Amazon briefly a few years ago for developing these, basically, cages for warehouse workers to work in. OK, who came up with the worker cages? It wasn’t Jeff Bezos. It was some functionary who’s trying to get ahead by marginally improving the margins and doesn’t really view the warehouse workers as people in the same sense that he’s a person, right?

All of the things that you might want to criticize about the social world, if you want to understand why those things are actually happening, who actually benefits from them and how, you can’t get there just looking at the millionaires and billionaires. You really have to zoom out and look with a wider lens at us. We’re the ones who really facilitate a lot of this stuff happening.

AL-GHARBI: Then the last point—sorry, I feel like I’ve been talking a lot, so my apologies.

KLUTSEY: No, no. That’s OK.

AL-GHARBI: Then one other reason why the taxing millionaires and billionaires thing is an insufficient (let’s put it that way)—an insufficient approach to social justice is because at the end of the day—so you tax the millionaires and the billionaires, you take a lot of money from them: OK, where is it going to go? There’s not actually an easy way to just take money from Jeff Bezos and give it to a poor person directly, right?

Instead, what ends up happening is it ends up getting filtered through governments and institutions controlled by us. We tend to take a nontrivial cut of that as it passes through.

An example that I highlight in the book is if you look at the early 20th century, when the symbolic professions were just getting created and income tax was just approved and philanthropy, as we currently understand it, was just getting underway, symbolic capitalists convinced (and coerced) a lot of the Gilded Age elites into transferring a lot of their money downwards. OK, but where did it go? As I highlight in the book, the primary wealth transfer that happened during that period was not from the rich to the poor. It was from the rich to the upper middle class. We took from the rich and we gave to ourselves in the name of social justice. That’s the same kind of pattern that you see recurring a lot.

One of the reasons why communism never worked is because communism is contingent on this idea that you have this morally pure, technocratic intellectual vanguard that would seize resources and means of production and then just allocate them fairly to everyone in society without taking anything extra for themselves, without taking anything extra for their loved ones in their own communities, and then just step down and live as the common people after they do this wealth transfer. It’s wild to expect that actual human beings—living, breathing, real people—would ever be able to do that. And, in practice, we never do.

Not only did that not work out the way that we said it would in the early 19th century, as the Gilded Age was winding down, it also (again) has never worked out in countries that embraced communism, for the same reason: because the intellectual vanguards who claimed to be morally pure representatives of the people just took a bunch of stuff and kept it for themselves and seized power and aggressively tried to silence dissent and so on and so forth.

That’s the same thing that we would expect to happen if there was this massive transfer through us in our own institutions in the name of social justice against …

I think that there’s plenty of compelling arguments for ways that the wealthy in society need to do more. But I would caution people to recognize the long history and ignoble history that symbolic capitalists have of taking money from wealthy people in the name of social justice and then reappropriating it for ourselves. It should be a thing that we’re all very mindful of as we talk about taxing the rich more.

KLUTSEY: Right. You anticipate this critique in your book: that this is about hypocrisy, that in a way we’re all hypocrites, right? It’s like, the one who is pro-immigration and wants a lot more openness with respect to people coming into the country would not want to have a foreigner living in their home. Or the environmentalist who talks about this stuff very fervently but isn’t changing anything in their actions, whether by the car they drive or how they use energy in their homes, to bring about change. In many ways, this is just telling all of us how hypocritical we all are in some ways. Right?

AL-GHARBI: Definitely, there is a lot of hypocrisy highlighted in the book. I think the important takeaway is that, whether or not we actually live the ways that we say we will, whether or not we’ll behave the ways that we say we do, this gap between what we profess and how we act—it actually matters for symbolic capitalists in a way that it doesn’t necessarily for other people. Because we have power, we have influence, we actually do shape the way a lot of things play out, and so how we behave and conduct ourselves actually matters. It tangibly matters for other people, including and especially the people we profess ourselves to be advocates for. How elites behave matters a lot for people who are genuinely vulnerable and disadvantaged in society, for people who are genuinely impoverished.

Yes, there is hypocrisy, but what I hope to underscore to people is that the hypocrisy is highly consequential. If we do care about this stuff, then we have some choices we have to make. We have to actually think a little bit more and take more responsibility.

I’ll say on this last point: One of the things that bugs me out a little bit sometimes about discussions of things like academic freedom is that traditionally, freedom was a package deal. Freedoms came with responsibilities. Rights came with duties. Privileges came with obligations. What you see in a lot of symbolic capitalist spaces today is there’s a lot of focus on their rights, on their privileges, on the things that they’re entitled to, on their freedoms—the freedoms they’re supposed to have, the autonomy they’re supposed to have and that other people are trying to curb. But there’s less focus on this question of, “Well, you have these freedoms: Are you exercising them responsibly? You have these rights or these privileges: Are you fulfilling your duties and obligations that are supposed to go with them? Do other people feel—”

If you’re like me, a professor at a land-grant public university, I’m paid for almost entirely through taxpayer funds. Am I actually serving my constituents, the constituents, as a public servant? Am I reflecting their values and their interests? Am I speaking to their needs and the things that they care about?

To the extent that we don’t care about those people, and we just feel like we’re entitled to our academic freedom and to the high pay that we enjoy relative to other people, and we shrug off this question about obligations and responsibilities—it’s no wonder, again, that there’s a lot of appeal for people who are out there with torches and pitchforks trying to burn the place down.

I think it’s incumbent on us, including and especially if we actually care about social justice, if we actually do care about helping the poor and helping the disadvantaged and stuff like this, to focus less on things like our freedoms and our rights and all of this, and really ask ourselves in an honest way: Are we actually fulfilling the duties and the obligations? Are we acting in responsible ways with the freedom and the resources that we’re given?

KLUTSEY: Yes, that’s really insightful. Now, you talk about the four great awokenings, and the one we’re currently experiencing, which is the fourth one, is winding down. What I find really fascinating is that—two things. First, how each awakening is generated by elite overproduction, which is a really interesting phenomenon that I’d love for you to expand upon. Secondly, there were major gains in socioeconomic equality, civil rights, trust in social institutions, civic participation from the 1860s to the 1960s, but those gains stalled or declined at the onset of the second awakening.

I’d love to get your perspective on why that is the case. First on elite overproduction, the phenomenon; and how the great awokening dims or diminishes a lot of gains that are made earlier on, from the 1860s to the 1960s.

AL-GHARBI: One of the things that I hope the book helps contribute to the discourse is that in a lot of the news coverage and punditry and some scholarship about the period of rapid change that kicked off after 2010, there is this perception among a lot of people that we live in unprecedented times, that almost all of this stuff is a product of kids these days or of changes in technology like social media and stuff like this. What I show in the book, as you noted, is that actually, this shift that we’ve seen after 2010 is actually a case of something, and that there have been three previous ones prior to this one.

By comparing and contrasting these cases, one, we can rule out a lot of popular theories about why things changed. We can know that it’s actually not the internet. The internet might have changed how this awokening played out, but it clearly wasn’t the main driver, because we had awokenings in the 1920s and the 1960s and so on, when we had no such thing. When cell phones were like fantasy. [laughs]

KLUTSEY: Sci-fi.

AL-GHARBI: Absolutely. Similarly, we had them play out a century before anyone in Gen Z was even born. It has nothing to do with the unique characteristics—there is some research that suggests that Gen Z people do have idiosyncratic preferences compared to older cohorts, but those clearly aren’t the thing that’s driving the awokening, because again, we had them before, a century before these children were even born. So we can rule out a lot of things.

AL-GHARBI: Then, by comparing and contrasting the cases, we can also get a lot of insight into questions like, Why do these things come about? Why do they end? Do they change anything? How does one influence the next? And so on. And so, on this question of why they come about, as I highlight in the book, there seems to be two big factors that predict when an awokening is going to happen.

The first one, as you said, is that they tend to occur in these periods of elite overproduction. That is when society is producing more people who feel entitled to an elite life, an elite standard of living, than society has the capacity to actually give those people the positions and lifestyles that they’re expecting. For instance, in the contemporary context, a lot of people grew up thinking that if they do the right things, if you go to school, especially at the right place, and you major in the right things and you keep your grades up and all of this, then you’re going to be entitled to something like a six-figure salary, comfortable life. You’ll be able to buy a house and buy a car and find a spouse and all of this kind of stuff and do as well as your parents or even better.

When you have a situation where you have growing numbers of people who did the “right” thing but are not able to find themselves—but are not able to actually live the kinds of lives that they envisioned for themselves—what happens is, a lot of these frustrated erstwhile elites start trying to condemn the people who are successful, the people who are at the top. Condemn those people and condemn the social order that they perceive to have failed them. In a way, these periods of elite overproduction provide the motive for an awokening.

But they don’t necessarily provide the means. This is because you need the second ingredient, which is that, as research from my adviser Shamus Khan and others shows, the fortunes of elites and nonelites tend to operate countercyclically. That means times that are good for elites are often rough times for everyone else; and then, on the flip side, times that are lean for elites tend to be pretty good for everyone else. They tend to be times when the labor market is tighter, people are being able to charge more for their wages and so on and so forth.

The times that are rough for elites, because they have to pay more for the services they’re consuming and things like this, tend to be good times for workers and ordinary people. This matters because a lot of times when there’s these moments of elite overproduction, there’s all these people who want to be elites, but they can’t. There’s all these elites who are not living the kind of life they expected. It’s usually tough to get anyone to care. No one’s breaking out their tiny violin for the poor scion of Ph.D. parents who wasn’t able to also get a six-figure job. No one cares, especially if times are good. No one pities that person: “Oh, poor them. They have to get a real job like everyone else. Boo-hoo.”

[laughter]

There are these moments when the trajectories of elites and nonelites collapse together. Things have been bad and getting worse for ordinary people for a while, and all of a sudden they’re bad for elites too. Those are moments when awokenings tend to happen, because you have the elites who want to burn down the system and condemn the people who are actually successful and you have a lot of other people in society who are also deeply frustrated with the way things are going, who are also committed to shaking something up, making something happen to make their lives better.

This provides the frustrated elites with basically more power than they would normally have to actually shake stuff loose and make stuff happen. Those are the moments when great awokenings are most likely to occur, as I argue in the book.

The second question was …

KLUTSEY: The gains that are lost in the aftermath of the 1960s as a result of the second great awokening.

AL-GHARBI: How I would explain that is that—the first thing to note is that the great awokenings in general tend not to benefit normal people very much. They especially don’t tend to benefit the genuinely desperate and vulnerable in society very much.

The reason for this is—let’s look at the period after 2010. What shifted? One thing that shifted is, there were a whole bunch of new jobs that were created in professional spaces. If you have a college degree, especially a degree from an elite school, and you happen to be Black or Hispanic or Indigenous or queer or disabled or something like this, there were new options created for you. New scholarship opportunities, new grants, new startup funds—all sorts of things.

That’s conditional on you already being an elite, basically. You already have to have your ticket punched. You need a good degree from the right school, and you need to be in the right kinds of symbolic economy hubs to take advantage of them. You need to be working in the right kinds of professions. It’s not like waiters who are Black or Hispanic suddenly got a whole bunch of raises on the basis of their race. It’s only in the symbolic professions where you saw a lot of these changes happen.

That’s just one example, but in general the big picture is that the changes that you see happening after awokenings tend to be restricted. The main beneficiaries are people who are themselves already well-off. These changes help elites who identify with historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups. It helps those elites better advance their own position or reproduce their own position, but it doesn’t really do much to help nonelites. It doesn’t change much about their lives, about their prospects. This is one reason why you don’t see much progress when awokenings happen.

So, why do you see the decline after the 1960s is the second thing. The reason that I argue in the book, part of the reason why the decline after the 1960s is because that really—after the 1960s, that was when the change really happened in the global economic order away from manufacturing and in favor of the symbolic professions.

The kinds of stories that we told ourselves at the time that transition was really kicking off is that, because we are committed to following the truth wherever it leads and helping the disadvantaged, and because we are committed to all of these kinds of social justice goals, that as people like us gain more power and influence, inequalities would be shrinking. Long-standing social problems would be getting better. People would have more trust in institutions because of all the great work that we’re doing for them.

That’s not what happened. Instead, again, the primary beneficiaries of the changes away from industry tended to be people who are already from elite backgrounds. And people who are more sociologically distant from the symbolic professions—so, people who live in small towns and rural areas or who live in flyover country or who work in jobs and professions that are not ours, people who have normal jobs of providing physical goods and services to people or things like this—those people did not see many benefits. In fact, in many respects, they’re worse off. Their communities are worse off.

AL-GHARBI: This is part of the thing that—and in fact, one of the things that’s striking is that when you look at various measures of racialized inequality—Black social mobility or the wealth gap or the income gap between Blacks and whites or the share of Black people who are incarcerated in the United States and so on—by a lot of these measures, the stats today are pretty close to identical or, in some cases, even worse than they were at the time that these shifts in the global economy kicked off in the late 1960s.

Why is that? Part of the reason why is because, as we shifted into this symbolic economy, things like having a college degree and having a college degree from the right school mattered more than it used to. Unfortunately, as a result of the way things have played out in America up to now, Black people are significantly less likely than white people to get into college, to complete college if they do get in. They’re less likely to pursue graduate degree programs, and they’re less likely to be graduates of elite schools like Harvard and Yale and so on and so forth.

An unfortunate consequence of shifting to focus on degrees instead of the way that—I guess, here’s the irony. The irony is, a lot of institutions stopped excluding people on the basis of race directly. It’s no longer legal, and it’s no longer even desirable for a lot of—a lot of people would actually find it disturbing if they understood themselves, for instance, to have hired someone based on racialized factors. If you demonstrated to someone that they seem to have done that, they would be horrified at themselves—as compared to in the ’50s, they’d be like, “Of course, yes. I did that on purpose. Absolutely.”

[laughter]

The irony is, there’s been this shift in values. There’s been this shift in laws that now make it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race, but because we now discriminate on the basis of educational credentials, especially elite educational credentials, and those are also distributed in this heavily skewed fashion, the ultimate outcome—actually, not a lot has changed. It’s still the case that, for the things that matter in the current economy, Black people are just less likely to have those things.

The gaps have persisted and grown, and they’re not driven anymore by overt bigotry and discrimination. They’re not driven anymore by legal exclusion. They’re driven by differences in who has credentials and who doesn’t. But the ultimate outcome is the same.

KLUTSEY: You also talk about the clustering and the hoarding of assets, if you will, because marriages, in particular, are happening within folks in the same socioeconomic class. There isn’t as much of this mixing that is happening as one might imagine.

KLUTSEY: I wanted to get your thoughts on, what do you think is the most underrated egalitarian city in the United States?

AL-GHARBI: Underrated egalitarian city . . . I don’t know. Unfortunately, I’m not super, super familiar with a lot of different cities other than—because I lived in a small town in Arizona and then I lived in Manhattan, which would not be on the list. [laughs]

KLUTSEY: Because you bring it up in the book, yes.

AL-GHARBI: No, I’m out here in Long Island. I’m not positive how to answer that question in a way that wouldn’t be kind of arbitrary.

[laughter]

But what I will say: I will say, though, based on my own experience, a lot of smaller towns, it is actually the case that—say if you’re a shoe salesman, it is actually the case in a lot of smaller towns, more rural areas—and not even just rural areas, though, but smallish to moderately sized towns. The gap between, say, a person buying a pair of shoes and the person selling that pair of shoes, the gaps between them culturally, socioeconomically, in terms of their life prospects, in terms of which schools their kids go to and all of that—those kinds of gaps tend to be a lot smaller.

It’s when you live in these really affluent knowledge-economy hubs, where—like in New York City, actually in New York State, for that matter, one out of every 12 people is literally a millionaire. But you also have among the highest poverty rates in the country, so you have this wild separation. And the same is true in California, where a comparable share of the population is millionaires, but you actually have, I think, the No. 1 highest rate of poverty in the country and high rates of racial segregation on top of the socioeconomic segregation.

I guess the way I would answer the question is that often it’s the less politically liberal places, the places that actually there’s less people who are overtly concerned about inequality, that tend to be more equal in practice, and there tend to be these smaller gaps between the rich and the poor. There’s more social mixing than in a lot of places like Manhattan, where people can be in the same physical space, but practically speaking, they exist in totally different social worlds.

There might be a janitor who cleans the building that Goldman Sachs consultants work in, but the janitor and the finance bros—they occupy the same physical space in the same city, in the same building, but there’s almost no interaction between them. They live in completely different social worlds. You don’t see that so much as you move away into places that are more distant.

KLUTSEY: Right. So how do you convince an elite that they’re elite?

AL-GHARBI: That’s hard. I had to dedicate a whole chapter of the book to that.

[laughter]

Because there is this tendency to, again, focus on the top 1% or the—Bernie Sanders used to say the millionaires and the billionaires.

KLUTSEY: The billionaires, right?

AL-GHARBI: Yes. Then he became a millionaire, and now it’s just the billionaires.

[laughter]

I think what you have to do, and what I tried to show in the book, is that for a lot of these problems, if you actually ask yourself in a serious way, “Who actually benefits from these inequalities? Who are the winners in the prevailing order? Who are the losers?” It becomes clear, if you really interrogate that question in a meaningful, empirical way, that symbolic capitalists are among the primary winners. That, again, you can’t really explain—even when you want to focus on the millionaires and billionaires or multinational corporations or insert-bad-guy-here—you really can’t explain how those people or institutions do the things they do without us.

I think walking people patiently through: “OK, so multinational corporations: You don’t like them. OK. When you talk about some terrible policy that multinational corporations are executing, who’s actually executing it? Who’s coming up with it? Who are the people who actually benefit from—?” When you walk people through these things in institutional terms, when you make the conversation more concrete, I think that helps.

Then the other thing that I spend a lot of time in the fifth chapter of the book doing—because there is this tendency for people who are elites to try to make themselves seem less elite by attaching themselves to some historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups. So, for instance, when people rail against the billionaires, they focus on Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. They don’t talk about Jay-Z and Oprah Winfrey, even though they are also billionaires, because there’s this implicit assumption that if you’re someone who’s from a historically marginalized or disadvantaged group, that you’re not an elite.

When we analyze elites and talk about elites, we talk about cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, neurotypical white men. [laughs] If you make that the focus, if those are the only people you focus on when you talk about elites, you end up with this really impoverished understanding of how the world works. In part because the elite strata of society is growing more diverse.

Even the white people who are elites are increasingly finding ways to themselves identify with some kind of disadvantaged group. You might be white, but maybe you’re female. Maybe you’re queer. Maybe you’re neurodivergent or disabled or something like that. So the strata of elites who don’t identify with some kind of marginalized or disadvantaged population is actually small and getting smaller every day. What I had to spend some time in the book also emphasizing is that the fact that someone identifies as an African American or is queer or something like that doesn’t mean that they’re not an elite.

Chapter 5 of the book walks people in depth through the ways that people try to leverage these identity claims to make themselves seem less elite, more meritocratic; to justify why they should be exempt from the same kinds of critique and rules that other people have to play by and so on and so forth. I think that that’s important for helping people both perceive some of the things that they’re doing and also to help them understand this point: that when we talk about elites, you, the reader—when I’m talking about elites for the purposes of this book, the top 20% to 30% of the population, symbolic capitalists—I’m talking about you. You, reader, you specifically, as well.

Helping people really internalize that point—that they are the subject of this book—is something that I had to spend a lot of time thinking about.

KLUTSEY: It comes through very, very nicely in the book.

KLUTSEY: Now, as we come to a close in this conversation, I want to look at something you say towards the end of the book, where you cite Teresa Bejan’s work that “equality is not something to be believed in but rather something to be enacted. It’s not a cause to be supported in the abstract. It’s something we do.”

My question to you is, How do we do equality?

AL-GHARBI: In the conclusion of the book, I tried to avoid—a lot of times when I read books, it’s like seven chapters of describing a problem and then one chapter that’s supposed to solve it. That last chapter is always really unsatisfying. [laughs] So I tried not to do that.

But this is a question—I think it’s actually the most important question. So part of what I’m hoping is that the book gets a conversation going about that question, which I feel is really important. I’m also working on a second book that’s going to really give more of a book-length treatment to that question. Because I feel like one chapter is not going to cut it, not in a satisfying way.

But I’ll give an example of how you can do equality instead of talking about it or thinking about it. When I lived on the Upper West Side and I was going to Columbia, there were public schools, about—the one that was closest to Columbia, P.S. 165, was overwhelmingly Black and Hispanic, mostly low-income people. That’s the school that I sent my own kids to because I’m a product of public school. I just sent my kids to the zone public school.

That wasn’t the decision that most of my peers at Columbia made: neither the grad students who had kids, let alone the faculty and the staff. Instead, they sent their own children to private schools. Often, ironically, private schools that had really aggressive curricula for teaching people about social justice while they cloistered them away from the poor and minorities.

If these folks are really committed to doing social justice instead of just thinking it, one thing that they could do is they could just send their kids to the zone public school. There’s actually a lot of research that shows that if they did that, it could help people. It could help people not just because you send their kids—there’s more butts in chairs; they get $50 more in taxes, however much more per student.

Instead, the main reason why it would matter is because, as Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and others like Raj Chetty have shown, when you have these social ties that get formed between affluent students and less-affluent students when they’re attending the same schools, that can be life-changing for less-affluent students.

It can help them form different kinds of social networks that keep them out of trouble, for instance. Or that underscore different kinds of aspirations that people can have. Or that can make them invest in their studies in ways that they might not have before because it wouldn’t be cool, in the social circles they would otherwise be in, to invest themselves scholastically.

When you have districts that have large numbers of less-affluent people and you have more affluent people who actually start folding themselves into those institutions, it can be game-changing. Also things like the PTA: You have more parental involvement once you have more affluent professionals who attend.

So this is really easy, in a way. It’s a really easy thing that, again, can help real people in the community in which you live—actual people in a real place. Instead of donating money to corrupt organizations like Black Lives Matter, they could just send their kid to the zone public school. It would be a lot easier: Instead of paying tens of thousands of dollars per year in tuition and manually hiking your kid to class—because they don’t have buses; the buses are for the zoned—and so on.

AL-GHARBI: So it’s really easy, on the one hand, but it’s also really hard. Because it’s about investing your own children into—and even though there’s a lot of research that shows that—when you look at who benefits from going to a school like Columbia, it’s not usually the people who are already affluent and well-connected. They don’t benefit much.

The people who benefit a lot are people from non-traditional-elite school backgrounds, because when they go to a school like Columbia, they get credentials that would make people take them seriously when they wouldn’t otherwise have even given you two seconds of thought. They learn this cultural capital, these ways of talking and carrying and presenting yourself that help you navigate through elite gatekeepers like people who are hiring and stuff like that. They form these social ties that they wouldn’t have had between other people who are also on a good trajectory.

If you’re someone who already comes from a relatively affluent background and you’re already on a winning path, you have parents who are involved and you live in a relatively safe and good community and you’re participating in these extracurriculars and all of that, for you …

There are studies that show, for students who got into both UPenn (University of Pennsylvania, which is an Ivy League school) and Penn State (which is a land-grant public university)—so there are people who got into both, and some people just choose to go to Penn State for various reasons. It turns out that their life outcomes in terms of income, career status, marriage, all of these kinds of things—there’s no difference. It doesn’t matter if you go to the Ivy League school or the land-grant school, for those people, because those people tend to already have the ingredients they need for success in life.

The point of this, the upshot, is that if these affluent parents just sent their kids to the less prestigious school with less—the chances that that would meaningfully diminish their children’s life prospects are actually pretty small. They probably wouldn’t. But even if the chance is just 1% more or less that sending your kid to this school could land them in disciplinary problems or would make it marginally less likely that they get into Harvard or something, even if you recognize that the objective probabilities are small that sending your kid to the zone public school would make their life worse off in some way, are you willing to roll the dice with your own children? [laughs]

For most people, the answer is no. Even if they could do a lot of good, potentially, by—if they and their colleagues and similarly positioned peers, even if they could do a lot of good by just sending their kid to the zone public school, and even if it wouldn’t actually come at a meaningful cost to their own kids and their own kids’ life prospects, the fact that it might, even if it’s a small probability—they just choose not to do it.

AL-GHARBI: This kind of a thing, this kind of a hope that we can mitigate a lot of these social problems without ever putting skin in the game, without ever personally changing our own life, our own aspirations, without ever personally adopting any kinds of risk for ourselves—somehow, again, just by taxing the super-rich—is the fantasy. That fantasy that we hold on to is one of the main things that prevents us from actually making progress on a lot of these problems that we’re committed to.

There are a whole bunch of low-hanging fruit like that, that people could do in practice if they were willing to incur even small amounts of risk or discomfort or changes to their life. The real question is, Do we actually have enough commitment to do those things? Because just because a belief is sincere doesn’t mean it’s important. You can be sincerely committed to social justice, but it might not be important enough to you to adopt these risks or make sacrifices to your aspirations.

This is the open question. I think we can take for granted that symbolic capitalists are sincere when they make these professions. The question is, How important is it to us? I think that’s a live question that we can only really answer through how we actually act and behave.

KLUTSEY: Thank you for that. I guess the upshot is the more mixing, the more integration across socioeconomic groups, demographics and so on, the better.

Professor Musa al-Gharbi, thank you so much for taking the time to join us on Pluralist Points. Really appreciate it. The book is “We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite.” I would encourage listeners to check it out. Very good book.

AL-GHARBI: Thank you so much for having me.

KLUTSEY: Sure thing.