Jada Taylor is a mother, a teacher, and an artist.

“I am born and raised in Lubbock,” Taylor said. “I went to Frenship, then graduated from Estacado. I taught for Monterey for a year, and now I’m teaching at Rise Academy.”

Taylor said she started out instructing art and has been teaching for six years now. On Saturday, she featured a new piece at the East Lubbock Art House Parkway Mural Festival, joining several other local artists to share food and music, calling attention to housing justice and accessibility in Lubbock.

“So in this piece, I really wanted to capture the reality of those who grow up in this environment,” Taylor said. “I lived a duration in Wofforth, I came to East Lubbock my ninth grade year and started out at Estacado, and [it’s] just a drastic change of realities.”

Standing in front of her mural, Taylor talked about a lack of walkable sidewalks, industrial factories next to neighborhoods polluted with smoke, and scattered abandoned buildings.

A complaint filed by the North and East Lubbock Coalition and LegalAid of Northwest Texas last year reported 38% of Lubbock’s Hispanic residents and 57% of Lubbock’s Black residents live within one mile of General Industrial zoning, negatively impacting property values in some of the city’s oldest neighborhoods.

“In this painting I really wanted to depict that, that these kids grow up here. They live in this environment every day, and it’s really difficult to be positive,” Taylor said. “It’s really difficult to have a growth mindset when you’re in an environment that is so just depleting.”

When East Lubbock residents made criticisms about the Leprino mozzarella cheese plant’s intentions to drain millions of gallons of treated wastewater from the factory to Lake Dunbar, proponents said to instead think about the benefits of around 600 new jobs in the area.

When the February agenda for the city’s planning and zoning commission held an item to discuss zoning for a waste transfer station, some nearby citizens suggested north or east Lubbock would have a better location, because of concerns that the station would allegedly have a negative impact on property values in the newer neighborhoods being built in southwest Lubbock.

“It’s like it’s almost screaming, like, I don’t care about you. I don’t care about your circumstances,” Taylor said. “And I know that Lubbock as a whole, that’s not the message that we want to send.”

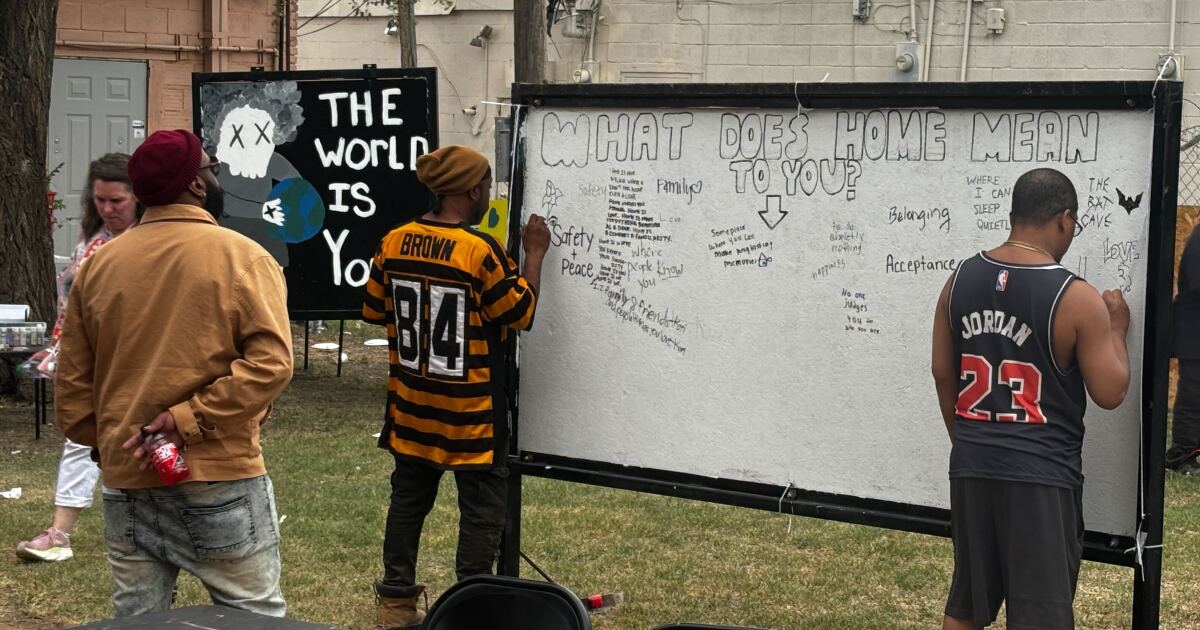

Many artists like Taylor assembled at the East Lubbock Art House for several days prior to finish their murals themed toward housing justice, joining with families to hear local musicians and paint together. One mural inspired visitors to express what “home” means to them, which was quickly covered with heartfelt notes and poetry. The tables covered in crock-pots of free food were quickly cleared.

Words like “belonging,” “acceptance,” and “safety and peace” were written on the wall. “Some place where you can make long-lasting memories,” and “no one judges you for who you are,” others wrote to describe what home means.

The paintings and conversation at the art house reflect a complicated reality for many in the community. Here in Lubbock, housing is less accessible than ever, particularly for middle and lower-income families.

Buying a home is considered by many to be one of the first steps to building generational wealth, but an August report from the Texas Comptroller’s Office cited the National Association of Realtors (NAR), noting the ability of someone with a median family income to afford median-priced housing is at its lowest level in the U.S. since 1985.

To track this, the Comptroller’s Office implemented the “Housing Affordability Index,” which measures the ability of a household earning the median family income to qualify to purchase a median-priced home.

A value of 1.0 indicates the median family income is equal to the amount needed to qualify for a mortgage loan for a median-priced home. The higher the ratio, the more affordable the housing market is in the area.

The Texas Comptroller’s Office report on housing affordability described “the center” of the housing affordability issue as a low supply of housing at price points that would be available to middle and lower-income earners.

Texas Comptroller’s Office Housing Affordability Index, Lubbock:

- 2015 – 2.22

- 2019 – 1.95

- 2022 – 1.56

- 2023 – 1.41

The recently released estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) show more than 23,300 housing units were built in Lubbock since 2010, almost 20% of the housing units in the city.

ACS data can also demonstrate what the household incomes, and housing burdens, look like in Lubbock.

According to the Census Bureau, the average median household income of the city of Lubbock is $54,451, compared to the median household income for the state of Texas: $75,780.

Meanwhile, the median home price for the city is $217,800. And almost 56% of home values were reported at $200,000 or more.

Around 65% of Lubbockites who pay a mortgage spend less than a fourth of their income on it. While almost half of the city’s renters report spending 35% of their income or more toward housing.

Other costs associated with owning a home have risen. Factors such as interest rates and an individual’s personal credit score, associated with the cost of borrowing for a home purchase, can serve as one barrier for many prospective buyers.

Average homeowners’ insurance rates in Texas rose by 6.9% in 2021 and 11.8% in 2022. According to the National Association of Realtors, Texas was one of the most expensive states for home insurance in 2024.

When costs increase for low and middle-income families trying to pay for housing, other expenses like healthy food can become lower priorities.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines households where more than 30% of their income is spent on rent, mortgage payments, and other housing costs as “cost-burdened.” Severely cost-burdened households have cost ratios of over 50%.

In 2022, 39% of Texas households were considered cost-burdened.

Paying to buy a home instead of renting was a significant financial burden before 2020, but the COVID-19 pandemic influenced both the cost of materials for building homes and other needs for families.

Within Black American renter households, 56.2% paid more than 30% of their income on housing costs in 2023, and 53.2% of Hispanic renter households were cost-burdened. According to the Census Bureau, 46.7% of white renter households were cost-burdened.

With the high costs associated with owning a home and the shortage of affordable houses, the total number of renters went up, creating a higher demand for rental housing units.

In Lubbock, the Census Bureau estimates a 14% lower home ownership rate compared to wider home ownership in the state Texas. Almost 38,000 Lubbockites moved into rental properties since 2021, while around 8,100 people moved into owned homes in that same time period.

The average gross cost of renting — rent, plus the average monthly cost of utilities and fuels adjusted for inflation — grew faster annually (3.8%) than median home values (1.8%) in 2023 for the first time in 10 years, according to the survey.

Around 50% of Lubbock homes are owner-occupied, but the ratio of renters to homeowners has been increasing. The cost of rent in Lubbock was almost $300 cheaper than the state’s average last year, with the average rent placed at $1,180.

Of the more than 23,000 individuals aged 15 or older who worked full or part-time with yearly incomes below the poverty level in Lubbock, 42% of them are single mothers.

Around 48% of citizens between 19 and 64 years old are employed, but 14% of them don’t have health insurance. Almost 22% of citizens 65 and older are still in the labor force, making a median income of $55,500 per year.

A higher frequency of rental properties provides an opportunity to address housing affordability on a surface level for growing cities, opening more dense spaces to more low and middle-income individuals and families, so they can get the housing they need.

Traditional single-family homes have also represented a challenge for those who want to see the housing industry and quickly sprawling metro areas make more responsive steps to address climate change. Each home requires more land and resources than a family would take renting space in a multi-family unit.

Thus, a vicious cycle is formed as trying to bring low and middle-income families into lower long-term housing costs and generational wealth by owning a home requires methods that contribute to climate change, and the risk of climate disasters can drive up costs for the home that makes it harder to bring people into a home of their own.

Low and middle-income properties are also open to predatory companies who can take advantage of tax credits to build cheaper rental housing that quickly dilapidates and impacts nearby property values, as well as placing already struggling tenants in an even tougher position, some who are likely to already be on social security assistance or section 8 housing vouchers.

Texans across both parties agree that housing reform is necessary in the state, but the next steps forward have not been without conflict, even here at home. Last year’s calls for change to local zoning regulations proposed amortization as a tool to address homes near industrial sites, met with “no action” from the assigned citizen’s committee.

That’s not to say things aren’t improving. After the share of Black homeowners in Lubbock dropped from 5% in 2011, ACS data has started to suggest an upturn, and Hispanic home ownership continues to climb. Average annual incomes have grown, and more people in Lubbock and across the state are increasingly aware of the racist history that institutionalized many of Lubbock’s disparities.

Danielle Demetria East is the founder and Executive Director of East Lubbock Art House and an artist. She and the rest of her team provide a venue for community events that can bridge divides and entertainment that is geared to inspire positive change.

“Home really means, like, care and safety and community. It’s something that I grew up with. So I feel like, if you grew up with that, the definition doesn’t really change,” East said, adding that many of the murals get into how the artists feel about what home means. “A lot of them, they really explore, like it’s not just like a physical space, but it’s this idea of like community, and care and love and connectivity.”

Correction: an earlier version of this story did not correctly list Danielle Demetria East’s title.

Taylor said East Lubbock neighborhoods would benefit from more local stores and restaurants that can improve property values and resident incomes, but her concern, as always, is for the kids.

“I’m proud to live in Lubbock, to have been from Lubbock, but we definitely do need to make a change for some of the kids that are also raised here,” Taylor said.

Taylor said she would like to see more entertainment and events like what the East Lubbock Art House has brought to the city. Better education for financial responsibility and public safety can follow, but it starts with hard conversations to make the next generation aware of the changes that can be made across the city.

“Sometimes we get caught up in wanting the change to be drastic and globalized and recognized worldwide. But we live everyday lives, and it’s okay,” Taylor said. “If I can interact with one more student or one more kid that I’ve not had the opportunity to interact with, I think that that, too, counts as making a difference.”

As a parent and a teacher, Taylor said a lot of responsibility is on Lubbock’s adults to have honest, daily conversations. Even if we make mistakes, Taylor said one of the most important parts of healing is showing children there’s value to be found in narrowing our disparities.

“Honestly, it’s day-to-day interactions,” Taylor said. “We’re human, and we absolutely crave physical anything, so just being present in those moments that you can be present, and if you see fit to have those difficult conversations or hard conversations, then do it.”

Taylor’s mural shows two kids facing each other with a barrier between them, but the barrier seems to be something the children could overcome with the right effort.

She added that communities in East Lubbock are not the only undeveloped neighborhoods in the city, and getting outside of our immediate areas to interact and make connections with others is how we can help the next generation defy what has divided Lubbock for so long.

“Little by little, teaching our children that we can do it together, that it’s okay to interact,” Taylor said. “I think once we reach a certain age in adulthood, that we have to acknowledge it, and we have to be a part of cultivating an environment that’s safe, not just for our children, but all children.”

At the East Lubbock Art House, community advocates continue the mission to ensure that “art is for everyone,” with regular events like community art classes, monthly art exhibitions, and special events to bring every corner of Lubbock together. More information can be found at eastlubbockarthouse.org.

Beyond the Art House, aid and advocacy work is also being provided by LegalAid of Northwest Texas, a nonprofit team of legal experts that provides free services for low-income individuals and families.

In October, the organization will be holding a Lubbock Community forum to provide citizens with further information on environmental justice and neighborhood rights, as well as more details on the services they can provide, with Disability Rights Texas, and the Clinical Programs provided by Texas Tech University School of Law.

Expert speakers will join representatives from Lubbock neighborhood associations, sharing their experiences and efforts to improve their communities.

The forum will take place on Saturday, October 26, from 1:00 PM to 5:00 PM at TJ Patterson Library, located at 1836 Parkway Drive.

More information and support with housing rights and housing advocacy for low-income Texans can be found at texashousers.org.

Further U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data can be found here.