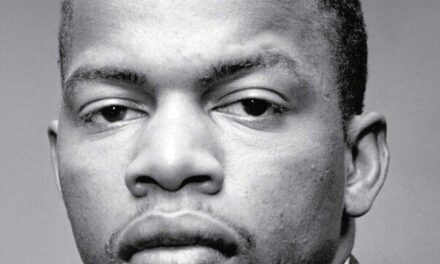

SAINT PAUL DE VENCE;FRANCE – SEPTEMBER: (FILE PHOTO) James Baldwin poses while at home in Saint … [+] Paul de Vence, South of France during September of 1985. (Photo by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images)

Getty Images

America needed James Baldwin (1924–1987) during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. With African American voting rights suppressed, with police violence overwhelmingly targeting African American communities, and with economic and health disparities outrageously out of proportion to those experienced by other races, Baldwin’s words exposed the nation’s structural racism.

With America fighting a present-day civil rights struggle, the country needs him again.

With voting rights for Black citizens again being assaulted. With Black History under attack. With police targeting African Americans for violence. With economic and health disparities outrageously out of proportion to those experienced by other races, Baldwin’s words have become familiar to new generations.

Thankfully.

Too bad.

In recognition of the 100th anniversary of Baldwin‘s birth on August 2, 1924, in Harlem, the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. presents the exhibition “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance.”

Baldwin was gay along with being Black, a double whammy in 20th century America. He was also poor.

Three strikes and you’re out, but not for Baldwin who would rise above the prejudices and obstacles the country placed before him to become one of the its great thinkers, writers–essays, novels, plays–and activists.

And one of the country’s great quotes.

“I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually,” Baldwin said, a facial to the “love it or leave it” crowd.

“Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”

“To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.”

{ if (!response.ok) { throw new Error(‘Network response was not ok’, preloadResourcesEndpoint); } return response.json(); }) .then(data => { const cssUrl = data.css; const cssUrlLink = document.createElement(‘link’); cssUrlLink.rel = ‘stylesheet’; cssUrlLink.href = cssUrl; cssUrlLink.as = ‘style’; cssUrlLink.media = ‘print’; cssUrlLink.onload = function() { this.media = ‘all’; }; document.head.appendChild(cssUrlLink); const hls = data.hls; const hlsScript = document.createElement(‘script’); hlsScript.src = hls; hlsScript.setAttribute(‘defer’, ‘1’); hlsScript.setAttribute(‘type’, ‘text/javascript’); document.head.appendChild(hlsScript); }).catch(error => { console.error(‘There was a problem with the fetch operation:’, error); }); } } loadConnatixScript(document); ]]>

“I can’t believe what you say, because I see what you do.”

“We can disagree and still love each other unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.”

‘Nina Simone with James Baldwin.’ Artist: Bernard Gotfryd. Gelatin silver print, 1965.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Through portraiture and biography, the one-room exhibition explores Baldwin’s legacy alongside his contemporaries in art, music, film, literature and activism. Contemporaries including Lorraine Hansberry, author of “To be Young, Gifted and Black,” iconoclast singer Nina Simone of “Mississippi Goddam,” and civil rights leader Bayard Rustin. Rustin was also gay.

“(The exhibition) presents portraits in a range of media and ephemera to reveal how Baldwin’s sexuality and faith, artistic curiosities and notions of masculinity—coupled with his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement—helped to shape this formidable figure,” exhibition consultant Hilton Als, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and “New Yorker” staff writer, said when the exhibition was announced. “Images feature Baldwin alongside other gay civil rights activists who affected his life, notably Rustin—the political activist and principal organizer of the ‘March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom’—and writer and playwright Hansberry.”

The exhibition features a powerful photo of Baldwin, the grandson of an enslaved person, and Rustin at the Selma, AL march to Montgomery.

The National Portrait Gallery presentation was inspired by the 2019 exhibition “God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin,” curated by Als. A book by the same title, edited by Als, is now available.

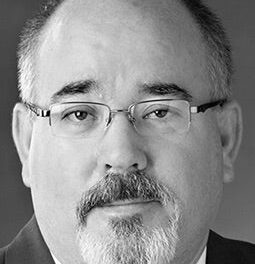

‘James Baldwin.’ Artist: Beauford Delaney. Pastel on paper, 1963. National Portrait Gallery, … [+] Smithsonian Institution. © Estate of Beauford Delaney by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator.

Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

“The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose,” Baldwin in “The Fire Next Time.”

“It took many years of vomiting up all the filth I’d been taught about myself, and half-believed, before I was able to walk on the earth as though I had a right to be here,” Baldwin from “Collected Essays: Notes of a Native Son / Nobody Knows My Name / The Fire Next Time / No Name in the Street / The Devil Finds Work / Other Essays.”

Baldwin considered himself “a witness” and used his writings to talk about America and its history. Attempting to ensure the United States “kept the faith,” Baldwin was often recognized for speaking out against injustice when other artists, collaborators and organizers were overshadowed.

“Baldwin was bolstered by a community of like-minded creatives… and his influence remains steadfast in the next generation of activists and artists,” exhibition curator and the National Portrait Gallery’s Director of Curatorial Affairs, Rhea L. Combs, said. “This exhibition seeks to highlight Baldwin’s significance through a collective portrait that not only offers a portrait of him, but also honors those who helped him become the man known for holding a mirror up to America and her promise.”

Few ever matched him in doing so. In bringing philosophy and receipts to the nation’s failure to act in accordance with its words, “all men are created equal,” and so on.

‘Bayard Rustin with Martin Luther King, Jr.’ Artist: Unidentified. Artist Gelatin silver print 1962.

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

“I imagine one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, they will be forced to deal with pain,” Baldwin wrote in “The Fire Next Time.”

“Freedom is not something that anybody can be given. Freedom is something people take, and people are as free as they want to be.”

“There are so many ways of being despicable it quite makes one’s head spin. But the way to be really despicable is to be contemptuous of other people’s pain,” from “Giovanni’s Room.”

The National Portrait Gallery exhibition includes works by artists Faith Ringgold, Glenn Ligon, and Lorna Simpson. Standing out is Beauford Delaney’s 1963 yellow portrait of Baldwin, one of the greatest portraits in American history when considering the artist, the subject, and their special friendship.

“It is certain, in any case, that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”

“The victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he or she has become a threat.”

“If I am starving, you are in danger.”

“Children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them.”

“This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance” will be on view through April 20, 2025.

His words have no shelf life.

Thankfully.

Too bad.

“Please try to remember that what they believe, as well as what they do and cause you to endure does not testify to your inferiority but to their inhumanity,” Baldwinfrom “The Fire Next Time.”